NAEPC Webinars (See All):

Issue 46 – May, 2025

Using Financial Modeling to Communicate the Benefits of Estate Planning Techniques to Clients in an Understandable Manner

By: Jerome M. Hesch, MBA, JD, AEP® (Distinguished); Brad Dillon, JD, LL.M.; Brandon L. Ketron, CPA, JD, LL.M.

Jerome M. Hesch is a member of Meltzer, Lippe, Goldstein & Breitstone, LLP in their Boca Raton, Florida office and is Special Tax Counsel to Oshins & Associates in Las Vegas, Nevada and Dorot & Bensimon in Aventura, Florida. He is the Director of the 50th Annual Notre Dame Tax and Estate Planning Institute, held on September 25-27, 2024, on the Bloomberg Tax Advisory Board, and a Fellow of both the American College of Trusts and Estates Council and the American College of Tax Council. He has published numerous articles, several Tax Management Portfolios on partnership tax, and co-authored a law school casebook on Federal Income Taxation, now in its fourth edition. He is a member of the NAEPC Estate Planning Hall of Fame and received the Lenard Silverstein Lifetime Achievement Award from Bloomberg Tax.

Jerome M. Hesch is a member of Meltzer, Lippe, Goldstein & Breitstone, LLP in their Boca Raton, Florida office and is Special Tax Counsel to Oshins & Associates in Las Vegas, Nevada and Dorot & Bensimon in Aventura, Florida. He is the Director of the 50th Annual Notre Dame Tax and Estate Planning Institute, held on September 25-27, 2024, on the Bloomberg Tax Advisory Board, and a Fellow of both the American College of Trusts and Estates Council and the American College of Tax Council. He has published numerous articles, several Tax Management Portfolios on partnership tax, and co-authored a law school casebook on Federal Income Taxation, now in its fourth edition. He is a member of the NAEPC Estate Planning Hall of Fame and received the Lenard Silverstein Lifetime Achievement Award from Bloomberg Tax.

He has presented papers for the University of Miami Heckerling Institute on Estate Planning, the University of Southern California Tax Institute, the Southern Federal Tax Conference, the AICPA, and the New York University Institute on Federal Taxation, among others. He participated in several bar association projects, including the Drafting Committee for the Revised Uniform Partnership Act. He received BA and MBA degrees from the University of Michigan and a JD degree from the University of Buffalo Law School.

He was with the Office of Chief Counsel, Internal Revenue Service, Washington, D.C. from 1970 to 1975, and was a full-time law professor from 1975 to 1994, teaching at the University of Miami School of Law and the Albany Law School, Union University. He is currently an adjunct professor of law, having taught courses in the past at the Vanderbilt University Law School, Florida International University Law School, the University of Miami School of Law Graduate Program in Estate Planning, Nova University School of Law and the On-Line LL.M. Programs at the University of San Francisco Law School and the Boston University School of Law.

Brad Dillon, J.D., LL.M. is a partner on the a16z Perennial team focused on tax, trust, and estate advisory, developing and implementing creative and comprehensive wealth transfer strategies that align with clients’ wishes. He reviews clients’ tax and estate planning documents to ensure that each plan accurately and holistically reflects the family’s philosophy and needs while maximizing tax efficiency and creditor protection.

Brad Dillon, J.D., LL.M. is a partner on the a16z Perennial team focused on tax, trust, and estate advisory, developing and implementing creative and comprehensive wealth transfer strategies that align with clients’ wishes. He reviews clients’ tax and estate planning documents to ensure that each plan accurately and holistically reflects the family’s philosophy and needs while maximizing tax efficiency and creditor protection.

Prior to joining a16z Perennial, Brad worked at UBS advising ultra-high net worth families to help them achieve their tax, estate planning, and philanthropic objectives. Brad began his career in private legal practice, most recently at Milbank in New York City, where he practiced in the firm’s trusts and estates department.

Outside of a16z Perennial, Brad is an adjunct professor at Fordham Law School, where he teaches courses on trusts and estates. In addition, Brad is on the editorial board of the Estate Planning Journal, where he is a regular contributor to the current developments column. Brad also co-chairs the multi-state practice section of the New York State Bar Association’s Trusts and Estates Law section. Finally, Brad is regularly quoted in the media on tax policy matters, and is a frequent lecturer and author, having published dozens of articles in industry-leading journals, including Journal of Taxation, Estate Planning, Trusts and Estates, and Leimberg.

Brad earned a BA in mathematics and philosophy from Indiana University (summa cum laude), a JD from UCLA School of Law, where he was an editor of the UCLA Law Review, and an LLM (Master of Laws) in taxation from NYU School of Law. Brad lives in New York City with his husband, twins, and dog.

Brandon Ketron, CPA, J.D., LL.M. is a partner at the law firm of Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A., in Clearwater, Florida and practices in the areas of Estate Planning, Tax and Corporate and Business Law. Brandon attended Stetson University College of Law where he graduated cum laude and received his LL.M. in Taxation from the University of Florida. He received his undergraduate degree at Roanoke College where he graduated cum laude with a degree in Business Administration and a concentration in both Accounting and Finance. Brandon is also a licensed CPA in the state of Florida. His email address is brandon@gassmanpa.com.

Brandon Ketron, CPA, J.D., LL.M. is a partner at the law firm of Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A., in Clearwater, Florida and practices in the areas of Estate Planning, Tax and Corporate and Business Law. Brandon attended Stetson University College of Law where he graduated cum laude and received his LL.M. in Taxation from the University of Florida. He received his undergraduate degree at Roanoke College where he graduated cum laude with a degree in Business Administration and a concentration in both Accounting and Finance. Brandon is also a licensed CPA in the state of Florida. His email address is brandon@gassmanpa.com.

Mr. Ketron has authored or co-authored dozens of articles for national publications and has spoken as a presenter on many occasions on estate and estate tax planning. He has also co-authored books on the subject of Internal Revenue Code Section 199A, the Employee Retention Credit and IRA Planning.

Mr. Ketron is also an integral member of the EstateView software creative team.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Factors Designed to Shift Value to a Trust That is Not Exposed to Estate Tax Without Having to Use the Gift or Estate Tax Exemptions

- Illustrating Estate Planning Techniques and the Grantor Trust Burn

- What Can Be Done To Reduce The Grantor Trust Burn?

- Tax reimbursement clauses.

- Terminate grantor trust treatment for the trust after the note is paid in full.

- Increase the interest rate on the note by up to 5% above the Applicable Federal Rate

- Invest some of the trust’s assets in municipal bonds or assets that appreciate and that will not be sold while the grantor is living.

- Invest trust assets in high cash value, low death benefit life insurance using conventional products or individually customized Private Placement Life Insurance (“PPLI”).

- Distribute some of the trust’s income producing assets to the beneficiaries.

- Use a private annuity sale to continue payments to the Grantor for life.

- Invest trust assets in encumbered real estate to shelter taxable income with depreciation losses, such as bonus depreciation.

- If Senior were married a SLAT could be used so that trust distributions can be made to the grantor’s spouse, but this is only viable if the grantor’s spouse does not predecease the grantor.

- Give the independent trustee the discretionary power to add the grantor as a beneficiary in a state like Nevada that has legislation that the grantor’s creditors cannot go after trust assets.

- Prepay the note in whole or in part before maturity date.

- Use a Self-Cancelling Installment Note.

- Retain additional assets and consider purchasing nursing home insurance and disability insurance to help account for unforeseen circumstances.

- Given that the discount is less significant than the burn, reduce the size of the valuation discount, which would likely minimize the audit exposure.

- Examples to Illustrate the Strategies That Can Be Used to Reduce the Impact of the Grantor Trust Burn.

- Alternative One – Reduce the Discount Rate to 20%

- Alternative Two – Retain Additional Assets

- Alternative Three – Increase the Interest Rate to 8.0% and use a Self-Canceling Installment Note

- Alternative Four – Turn off Grantor Trust Status in Year 20 After the Note is Repaid

- Alternative Five – Change Term of Note to Ten Years

- Valuation Adjustment Clauses

- Illustrating Private Annuity Sales

- Appendix

I. Abstract

An estate planning proposal can often be confusing because it involves the integration of several separate factors. Furthermore, the proposal must be flexible because of a future change in circumstances. This article is designed to first address the four primary factors used to shift value to an irrevocable trust that is not exposed to the gift and estate taxes. The next objective is to illustrate how these four factors accomplish the wealth-shifting objective. Rather than verbally explain how these four factors work, it is far easier for the potential client to understand the impact using simple to follow examples that illustrate the fiscal impact each year over the individual’s estimated life expectancy. In effect, the use of simple to follow numerical illustrations allows the adviser to communicate a planning proposal in an understandable manner. The use of year by year illustrations also demonstrates that some of the four wealth shifting factors are more effective for clients with a short life expectancy while other factors are more effective for clients with a longer life expectancy. This article also demonstrates that if a client has a long-life expectancy the grantor’s obligation to pay the income taxes on a grantor trust’s taxable income is the most important wealth shifting factor because of the compounding over a prolonged period. Because the grantor’s obligation to pay the income taxes on trust income depletes the grantor’s retained income-producing assets, it is entirely possible that this obligation will fully deplete the grantor’s retained assets while the grantor is living. Therefore, the final portion of this article will illustrate several adjustments that can be made to the planning proposal or made after the plan has been in place to mitigate the depletion of the grantor’s retained assets.

II. Introduction

When discussing estate planning strategies with clients, it is imperative to discuss the benefits of planning versus not planning. Sometimes the benefits can be showcased with an easy example or two, as when discussing the use of the lifetime exemption to make taxable gifts with no gift tax. Other times it takes a more complex analysis involving financial modeling to determine if the proposed plan is appropriate for the client’s financial situation. This can involve the use of spreadsheets or illustrations to communicate the gift and estate tax benefits of a proposed planning technique. Often, just setting forth the results fails to communicate the impact of all the factors that impact the plan.

In addition to explaining the gift and estate tax benefits of a proposed planning technique, an important objective of financial modeling is to communicate how these tax benefits work in an understandable manner. If a client understands the technique, they can become involved in the design of the estate plan and help make decisions on how much to “give away.” Illustrating the estate and gift tax savings of a particular technique is not overly complicated. However, an important part of any estate plan is to make sure that the client does not run out of assets later in life.

Through the use of financial modeling the common techniques used by estate planners can be illustrated in a way that allows the client to understand the factors that influence the shift of wealth to future generations without exposure to estate and gift tax, and the impact these factors have on the client’s retained assets that will be needed to support the clients for the remainder of their lives. If a client can understand or at least have a clear picture of the financial impact of the estate plan, the question of “Am I giving away too much?” that often holds up many estate plans, can be eliminated.

These materials will discuss the factors involved in an estate tax plan, provide illustrations to illustrate the estate tax plan and the impact it will have on the client’s retained assets, including the impact of the client’s obligation to pay income taxes on the grantor trust’s income (the “Grantor Trust Burn”), which are used in most estate tax planning situations, and discuss what can be done to eliminate the financial hardship caused by the Grantor Trust Burn.

Modeling strategies not only provide tangible numerical data for clients, but often provide deep insights into the strategies we propose. These materials will use financial modeling to highlight a few of those insights and hopefully provide readers with practical planning tips to help their clients make better decisions around their planning, and make decisions that align more closely with their client’s spending needs and financial goals.

III. The Factors Designed to Shift Value to a Trust That is Not Exposed to Estate Tax Without Having to Use the Gift or Estate Tax Exemptions

A. The four factors are listed below, and each is discussed in more detail in the discussion that follows:

1. Valuation Discounts

2. Freezing the Current Value of Assets

3. Financial Leverage

4. Using Grantor Trust and the Grantor Trust Burn

B. Valuation Discounts

The use of discounts to value assets subject to estate tax or that will be transferred by gift are often highlighted by planners as an estate and gift tax savings technique. For example, an interest in a Limited Liability Company or a Limited Partnership where the client does not control the voting interest, can be discounted for lack of control. Further, those ownership interests can be further discounted for lack of marketability or other factors. The discount value must be determined via an appraisal by a qualified professional based on what a willing buyer would pay a willing seller for an interest in the Company. These discounts can range anywhere from 15% to 40%, or even higher in some situations. Unreasonable discounts are commonly audited by the IRS and undergo close scrutiny.

A common estate planning strategy will be to sell or gift a minority interest, or a non-voting interest, in a Limited Liability Company or Limited Partnership. For example, an LLC holds $10,000,000 worth of assets and the membership interests consists of a 1% voting interest and a 99% non-voting interest. The client can transfer the 99% non-voting interest that will be valued for gift tax purposes at less than $9,900,000 due to lack of control and lack of marketability. A valuation expert may value the interest at a 35% discount so that the 99% non-voting LLC interest is valued at $6,435,000 resulting in a shift of $3,465,000 without the use of estate or gift tax exemption.

As illustrated in the examples that follow, valuation discounts are a one-time benefit and often the least significant factor in effectively shifting wealth outside of the estate over the long term. Financial modeling can illustrate this, and many planners may choose to be less aggressive with discounting once this is understood. Because large discounts invite an IRS audit, clients may be inclined to lower the discount, thus reducing their audit exposure.

C. Freezing the Current Value of Assets

A common theme of an estate planning technique is to freeze the value of the client’s existing assets and allow for the growth in those assets to pass outside of the estate. This can be done by selling appreciating assets to a trust for a promissory note that pays interest at the Applicable Federal Rate or by using a Preferred Partnership Freeze where the principal balance of the note, or the value of the preferred interest is not increasing in value but remains constant. This allows for growth above the stated interest rate on the note, or the preferred rate of return on the partnership interest to pass outside of the estate and limits the value of the client’s estate at its current level.

D. Financial Leverage

As mentioned above, freezing the value of the client’s estate by selling assets to a trust outside of the estate in exchange for a promissory note in which the principal balance does not increase, or for an annuity, or entering into a preferred partnership arraignment where the preferred interest, the promissory note or the annuity do not increase in value is a common estate planning technique.

These techniques all require interest or a preferred return to be paid back to the client. On loans, this is normally based on the Applicable Federal Rate in effect when the note is given, which is based on Treasury Bill rates, which have historically been lower than the expected rate of return produced by the assets transferred. To the extent that trust that is outside of the estate can achieve a return, or growth in assets, which exceeds the interest rate, or rate that is used to calculate the annuity or other payment coming back to the grantor, a shift in wealth occurs.

For example, a $10,000,000 asset is sold to a trust outside of the estate in exchange for a $10,000,000 promissory note paying interest at 4%. If the trust’s purchased assets grow at 8% in the first year, the Trust would have grown by $800,000, but the Trust is only required to pay back $400,000 to the client. Thus shifting $400,000 of wealth outside of the estate.

E. Using Grantor Trusts and the Grantor Trust Burn

The use of Grantor Trusts is crucial to many estate planning techniques. Under a Grantor Trust, the grantor is considered the owner of the assets for income tax purposes only. This allows for two major advantages: (1) a sale of assets to a grantor trust is disregarded for income tax purposes, meaning it is not considered to be a gain recognition event that would trigger income taxes as if the asset was sold to a third party, and (2) the grantor pays the incomes tax on the trust’s income without the payment of the trust’s taxes being considered a further gift to the trust. This allows for assets outside of the estate to grow income tax free, while the client’s assets are further depleted by paying the taxes on the Grantor Trust’s income.

This is a powerful tool, and, as shown in the illustrations that follow, must be considered in any estate tax plan because as the assets in the trust continue to grow in value so does the client’s income tax burden. Over time this can cause a significant reduction in the client’s estate. This can be a great thing, or if not appropriately planned for can become a significant financial burden to the client by depleting the client’s retained assets so that they cannot continue to live the lifestyle that they have become accustomed to or pay for nursing or other expenses. This can lead to a very unhappy client!

Many of the commercial software programs available today do not consider the depletion of the client’s retained assets, and it is often overlooked or dismissed by planners because they simply assume that grantor trust status can be turned off before it becomes a problem. This is a mistake! The impact of the Grantor Trust Burn must be considered in any financial modeling of an estate tax plan, and as shown in the examples that follow the Grantor Trust Burn is often the most significant factor in the long run that depletes the client’s retained assets.

If the Grantor Trust Burn is appropriately illustrated, the plan can be designed in a way that allows the planner and/or the client to consider alternatives that can reduce the impact of the Grantor Trust burn if necessary so that the client can continue to have the lifestyle they have become accustomed to. These alternatives are discussed later in the materials.

IV. Illustrating Estate Planning Techniques and the Grantor Trust Burn

A. Straight Gift of Assets to a Grantor Trust

Assume the following facts:

Senior, age 70 and single, currently has $20,000,000 of income producing investment assets. This year Senior spent $500,000 of his investment income for personal living expenses in addition to spending the income from social security and his pension plan. It is estimated that his personal living expenses will increase by 3% each year.

Assume an effective 30% Federal and state income tax rate for a combination of capital gains and ordinary income.

Senior wants to make a gift to a trust for the benefit of his children and asks how much he can give away given the above assumptions. The gift tax exemption for 2025 is $13,990,000.

For purposes of the illustrations, assume a conservative rate of return of 5% on Senior’s investment assets, all of which is taxable based upon 30% of the amount of income in this example.

Financial modeling allows the planner to consider the depletion of the grantor’s retained assets by: (1) the grantor paying the income taxes on the grantor trust’s income and (2) the amounts the grantor spends on personal living expenses.

Each of the following gift examples is designed to determine the point in time when these two wealth depletion factors mentioned above exhaust all the grantor’s retained assets while the grantor is still alive.

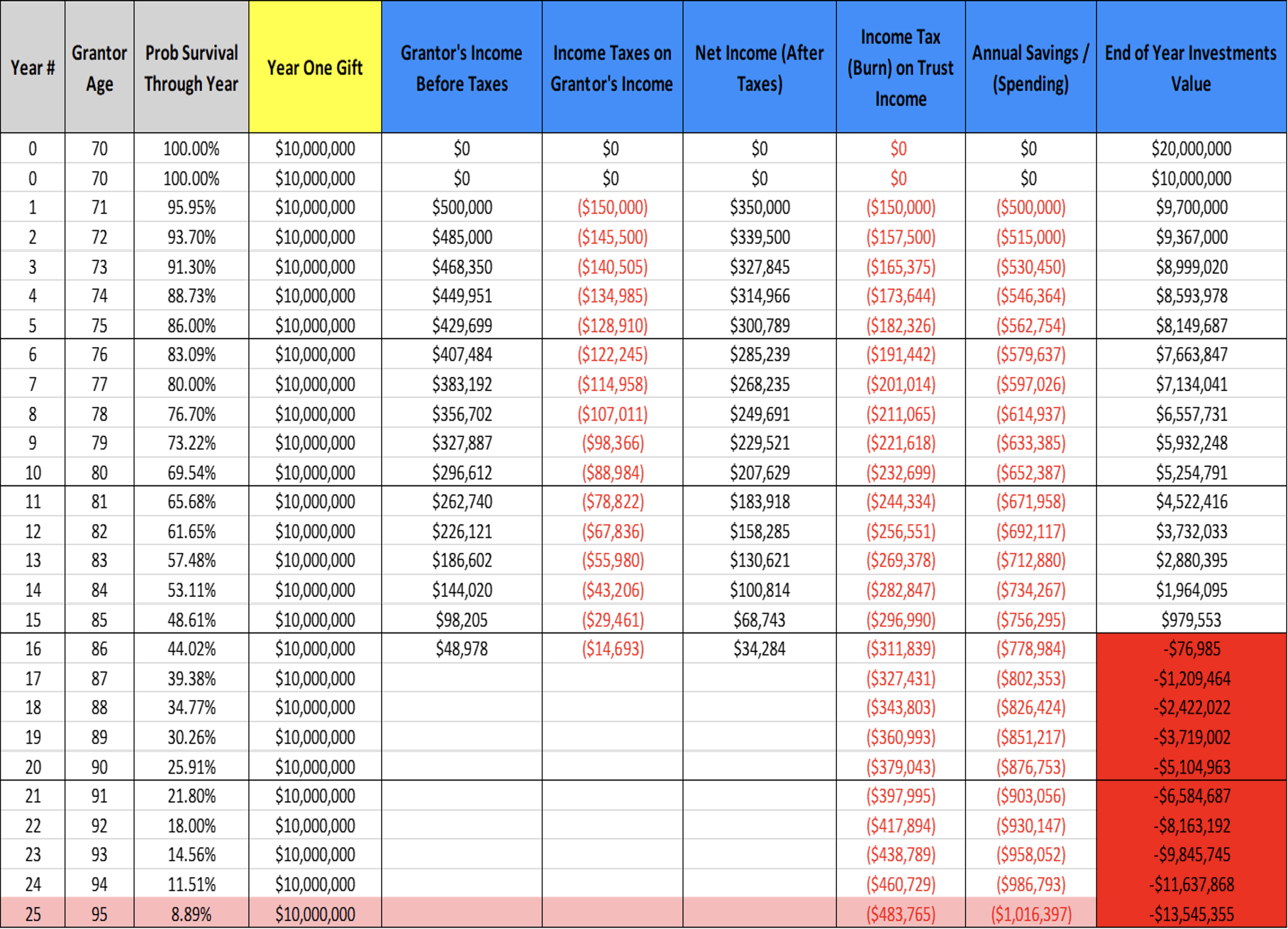

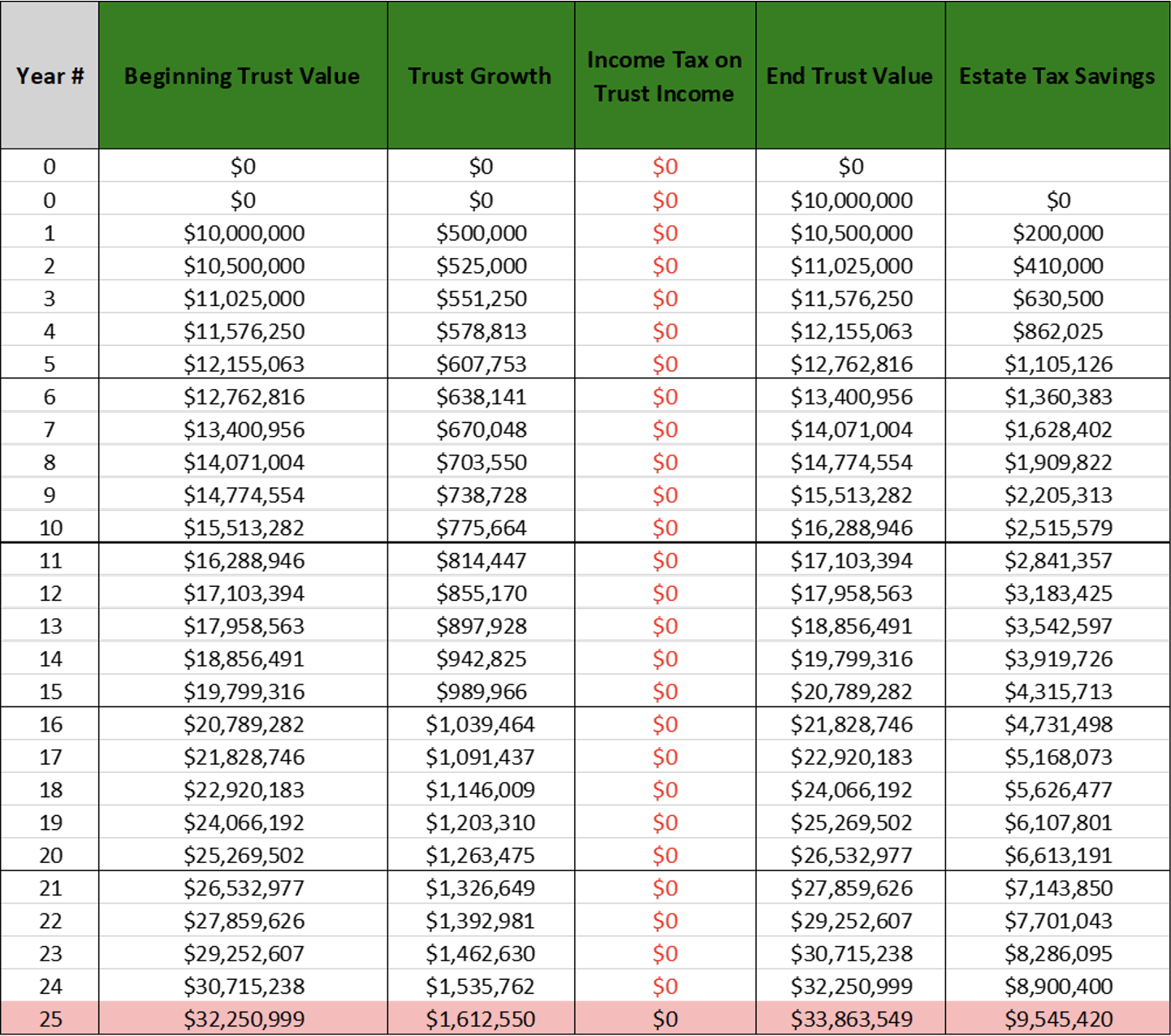

1. Example One – Senior gifts $10,000,000 of assets and retains $10,000,000 assets.

As shown in the illustration below, in the first year, Senior received $500,000 of income from the retained $10,000,000 of assets and paid $150,000 of taxes on that income. After paying $150,000 of taxes on the Trust’s income and spending $500,000 on personal consumption, Senior had to invade $300,000 of his retained $10,000,000 of assets. As the income-producing assets in the grantor trust increase in value, the Grantor Trust Burn will also increase.

The payment of the income taxes by Senior on his income and the Trust’s income (the “burn”) and Senior’s personal consumption totals $800,000, and that amount exceeds Senior’s $500,000 of income from his retained investments. As the Trust continues to build value, the exhaustion of Senior’s retained assets occurs at age 86 – the perfect estate plan if Senior does not live past 86! However, most wealthy individuals will live well past age 86. Knowing this, Senior may prefer to gift less of the $20,000,000 and retain more of the $20,000,000.

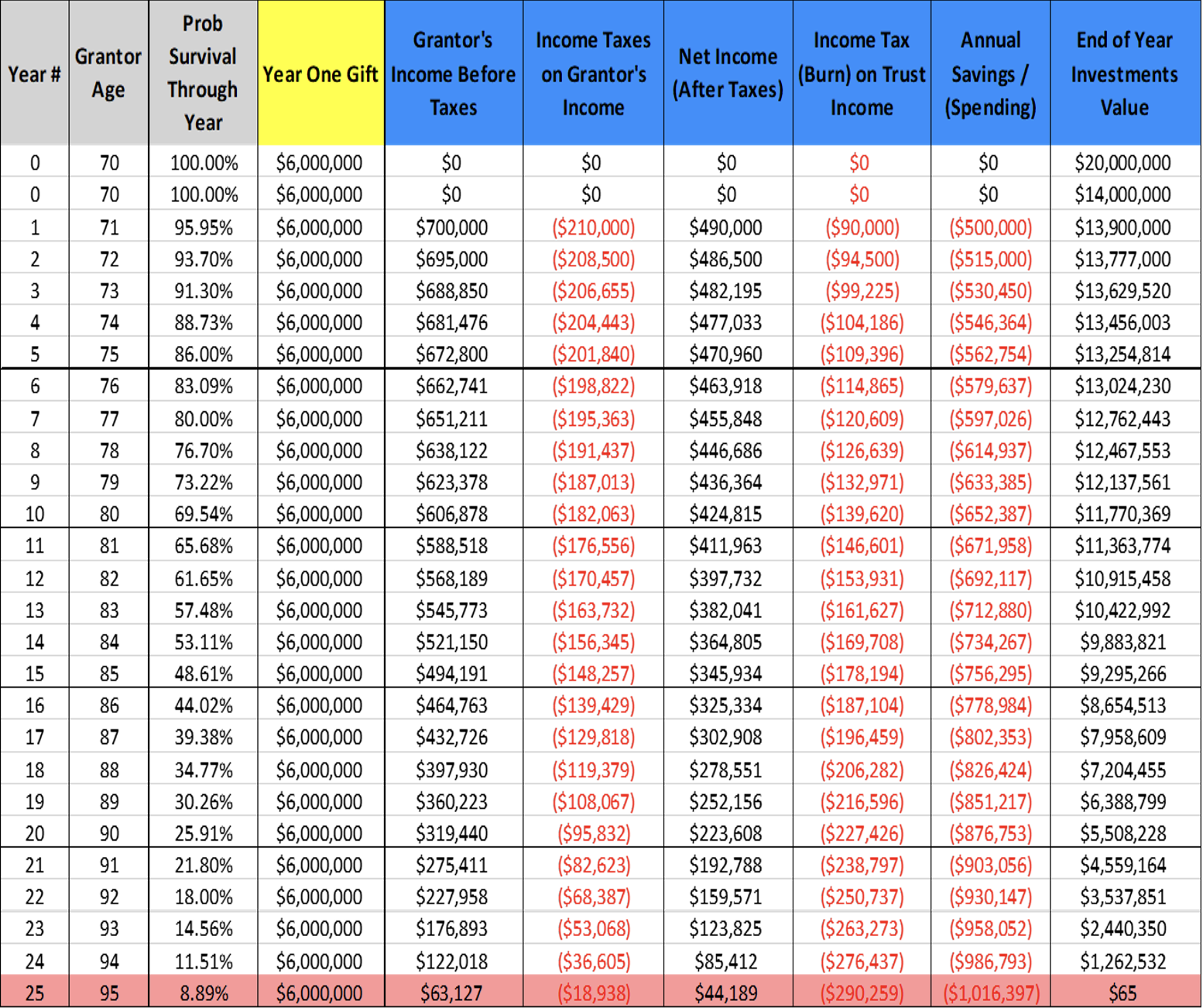

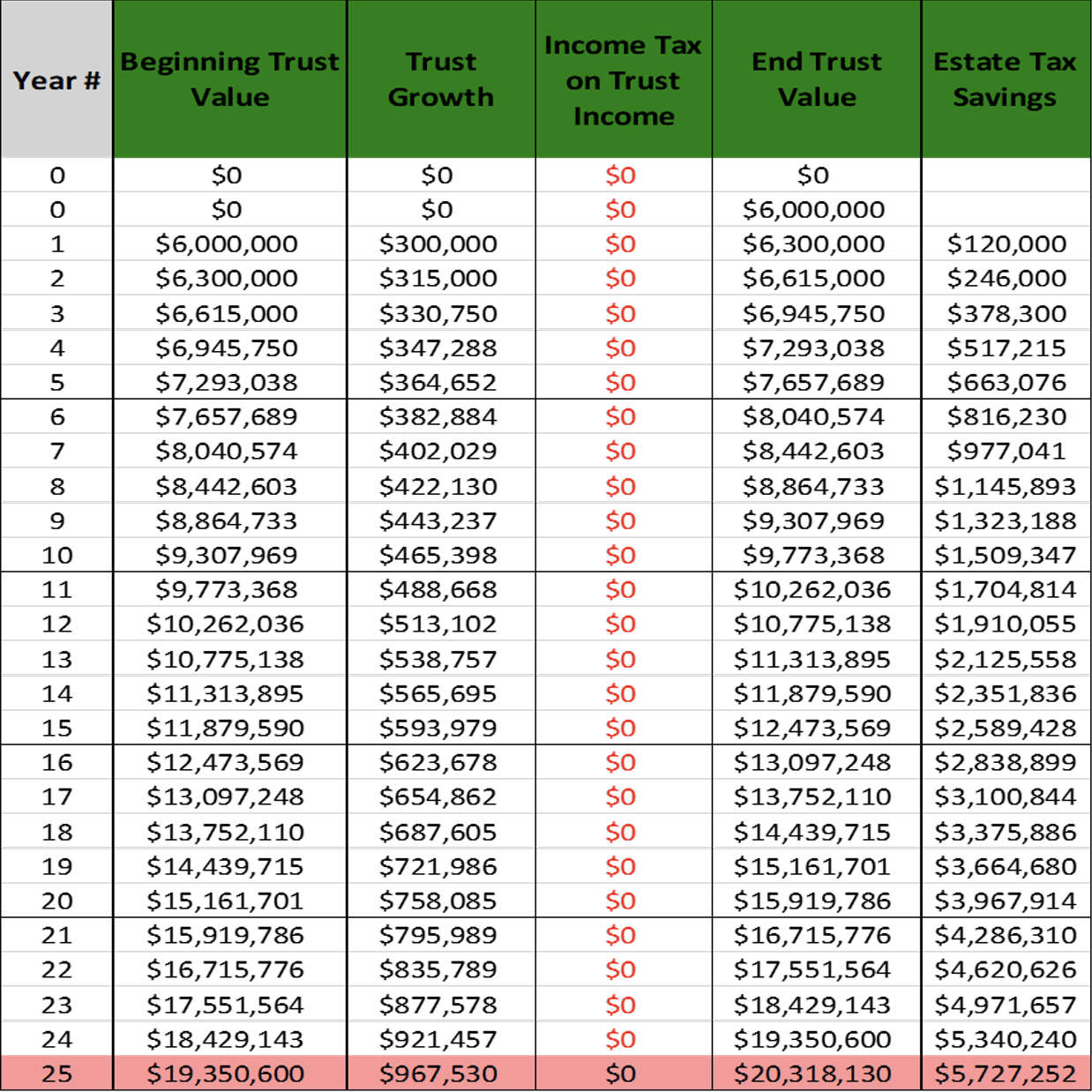

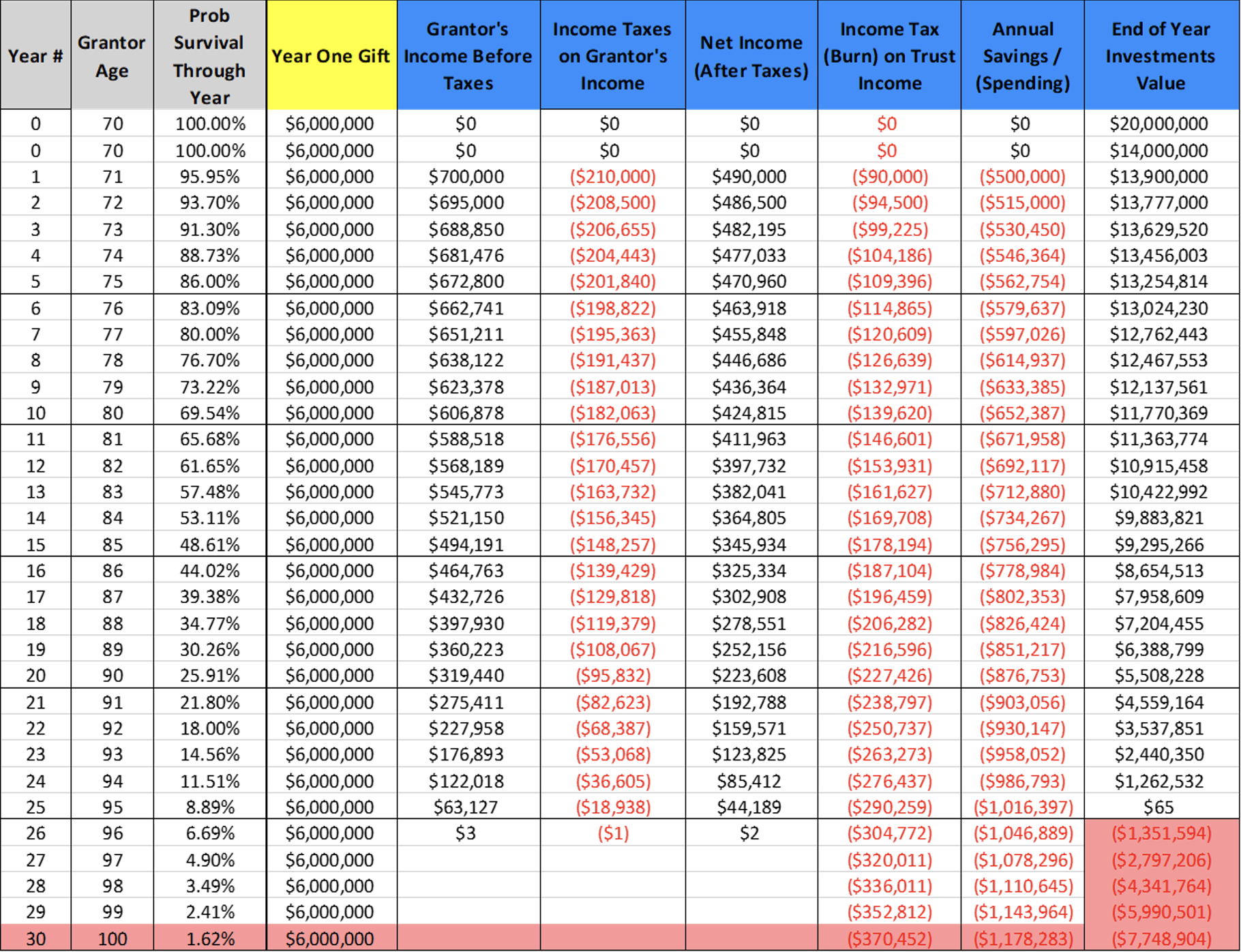

2. Example Two – Gift of $6,000,000

Although it seemed intuitive to maximize the use of the gift tax exemption when advising the client, the illustrations demonstrate that to maximize the gift tax exemption, Senior would need more than the existing $20,000,000 of investment assets.

The next example demonstrates the impact of the wealth depletion factors if Senior gifted $6,000,000 of assets and retained $14,000,000 of Senior’s income-producing assets. In this situation, Senior’s retained assets are exhausted if Senior lives to age 95.

At age 95, based upon our assumptions, Senior would be left with $65 by only making a gift of $6,000,000 to the grantor trust and retaining $14,000,000. This may be a surprising result for many planners.

So, what caused the depletion of Senior’s retained assets? The Grantor Trust Burn! As the Trust grows in value the income taxes that Senior pays on behalf of the grantor trust increase each year. In addition, Senior had to pay for his own personal living expenses and income taxes, all of which drive down the value of Senior’s estate, and we end up with $65 remaining. Again, we have designed the perfect estate plan as long as Senior dies by age 95, but of course Senior will ask what happens if he lives past age 95?

Some clients may be comfortable with the above given that there is only a 6.69% probability that a 70 year old will live to age 95, and there will likely be other things that can be done to reduce the impact of the Grantor Trust Burn, as discussed further below, in order to enable Senior to live comfortably until Senior’s death. However, Senior is conservative and wants to see a scenario where less is given away, so that Senior can retain sufficient assets past the age of 100.

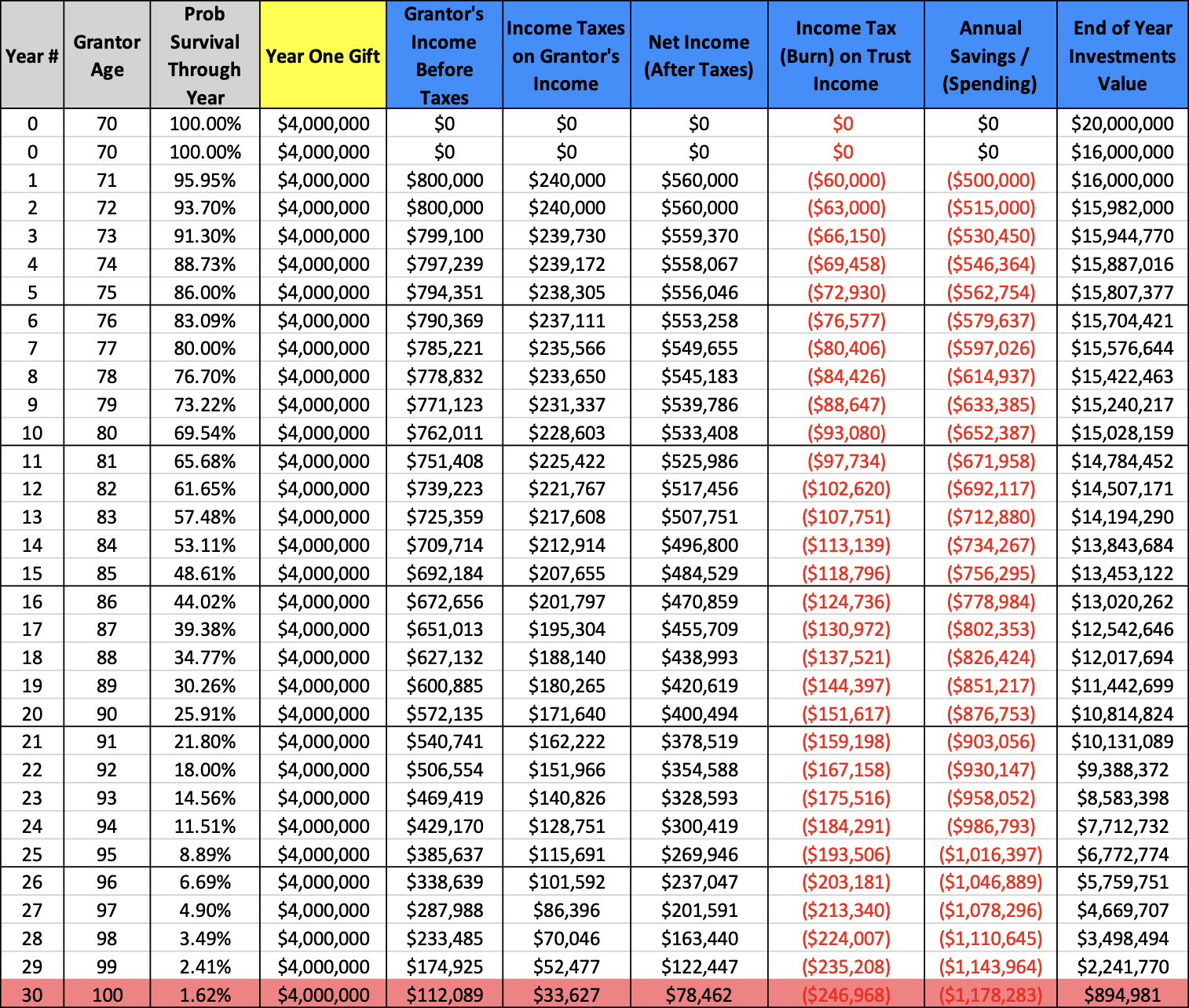

3. Example Three – Gift of $4,000,000

The next example illustrates Senior gifting $4,000,000 of assets and retaining $16,000,000. As shown below, at age 100 Senior still has $894,981 of retained assets. Senior may now feel more financially comfortable. If Senior’s investment assets were more than $20,000,000, say $30,000,000, then Senior can consider using the entire $13,990,000 gift tax exemption for 2025.

4. Key Takeaway – Do not over plan!

Using illustrations such as the above allows the client to be involved with financial design of the estate plan and understand exactly what they are doing by making a specific gift, and the impact that gift will have on their estate plan.

As shown above, planners would be making a serious mistake of advising a client to gift their entire $13,990,000 exemption amount, simply because it is possibly going to be reduced in 2026. It might seem counterintuitive to not take advantage of the bonus exemption while it is available, but if you have somebody with investment assets below $30 million, you can show them that they should forget about maximizing the use of their gift tax exemption. We want to make sure that the client has enough money for the rest of his or her life if he or she lives to the age of 100. A lot of planners are making these $10,000,000 to $12,000,000 gifts today without preparing the financial spreadsheets to show what a financial disaster it can be.

In Section IV below are a list of several alternatives that can be used to mitigate the impact of the Grantor Trust Burn on the client’s retained assets. Some of these may be appropriate and allow for the grantor’s retained assets not to be depleted as quickly; however, one may not even know that the alternatives are needed unless or until a financial analysis is performed.

Now if someone has a hundred million dollars of investment assets, taking advantage of two $13,990,000 taxable gifts with no gift tax is viable. But even at this level of wealth we can burn out retained assets after 25 or 30 years.

Clients with this level of net worth may need to do additional planning such as an installment sale to freeze the current value of their estate, take advantage of financial leverage as well as the Grantor Trust Burn to reduce their estate and minimize potential estate tax liability. So let us look at an installment sale transaction in more detail.

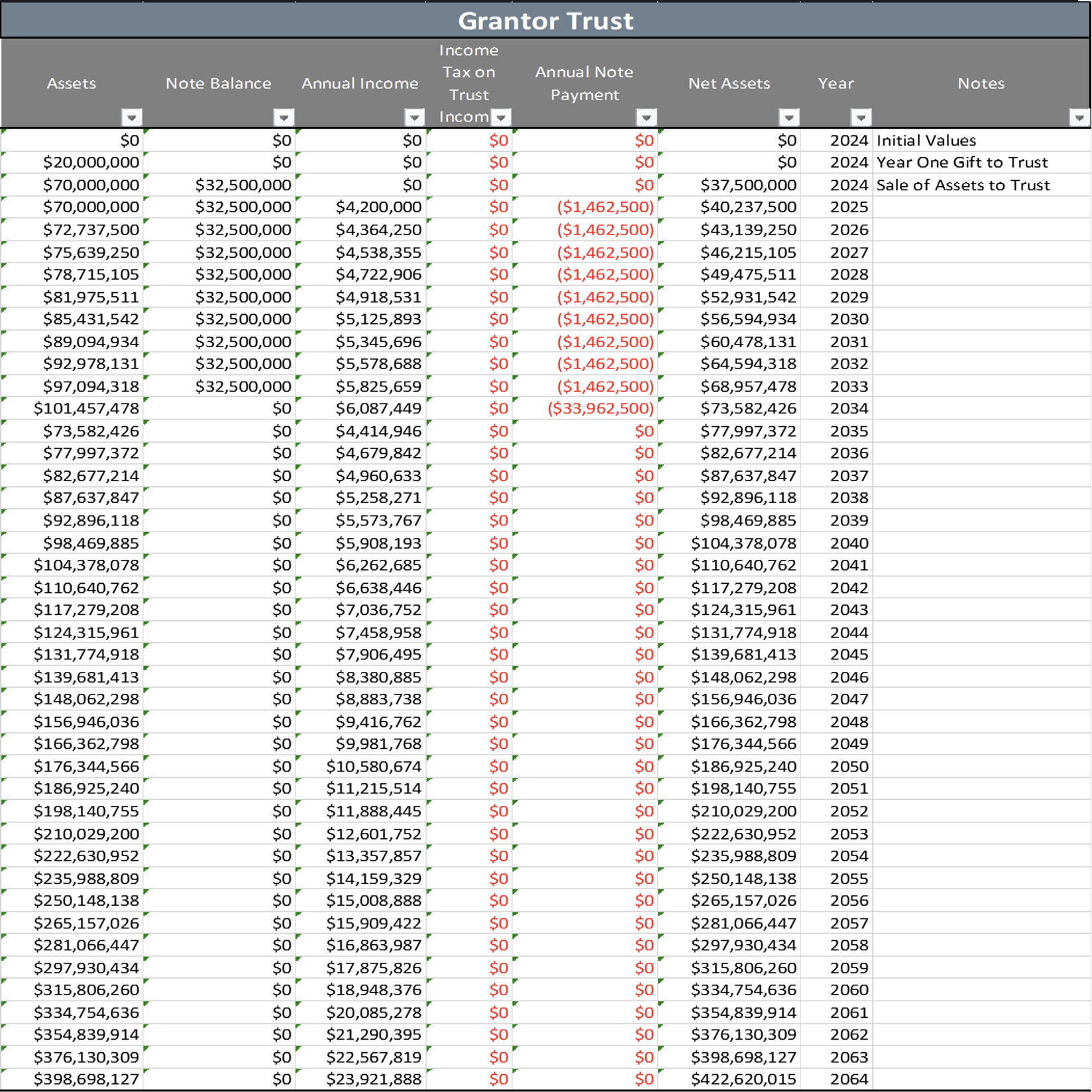

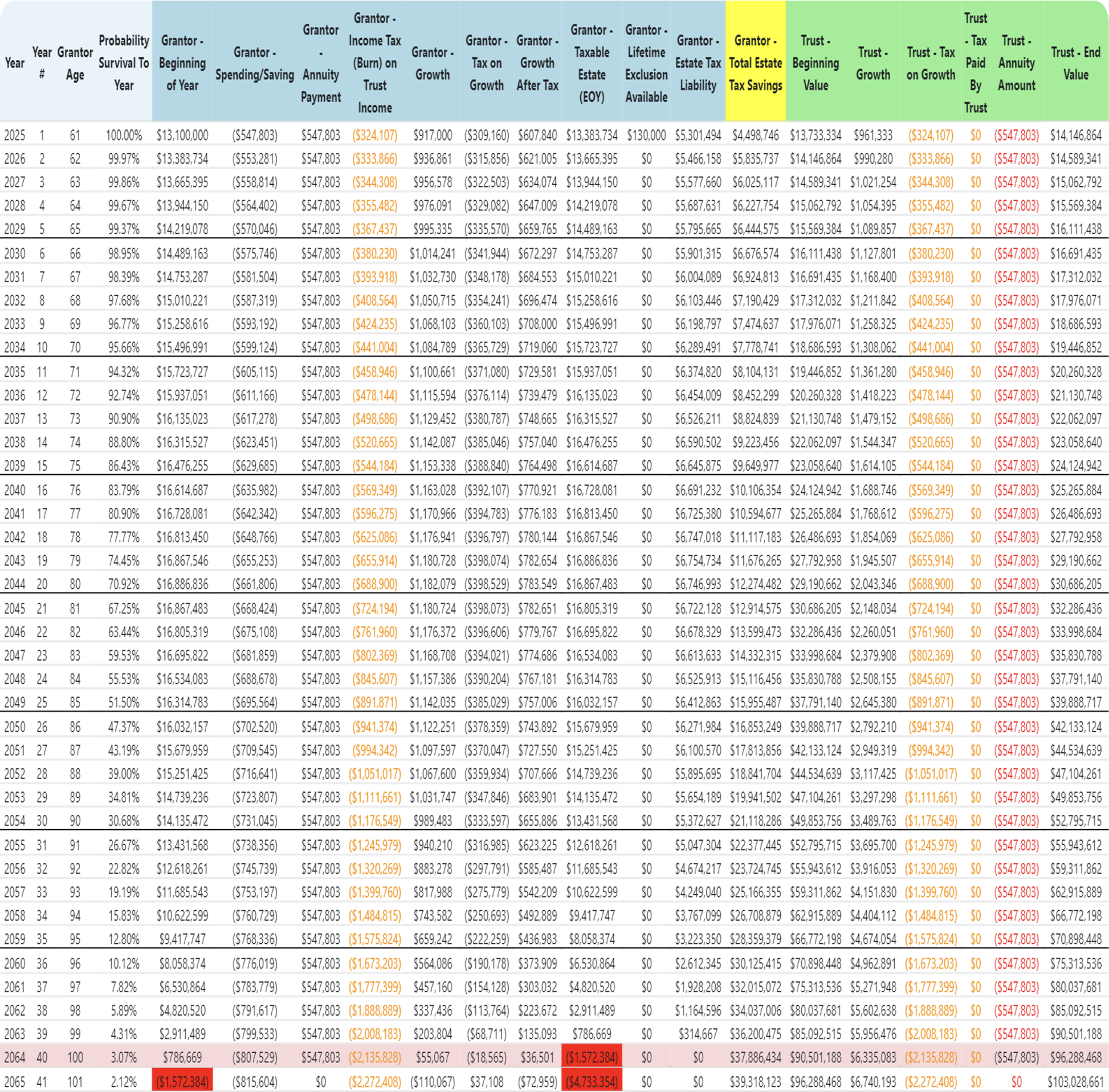

B. Illustrating an Installment Sale to a Grantor Trust

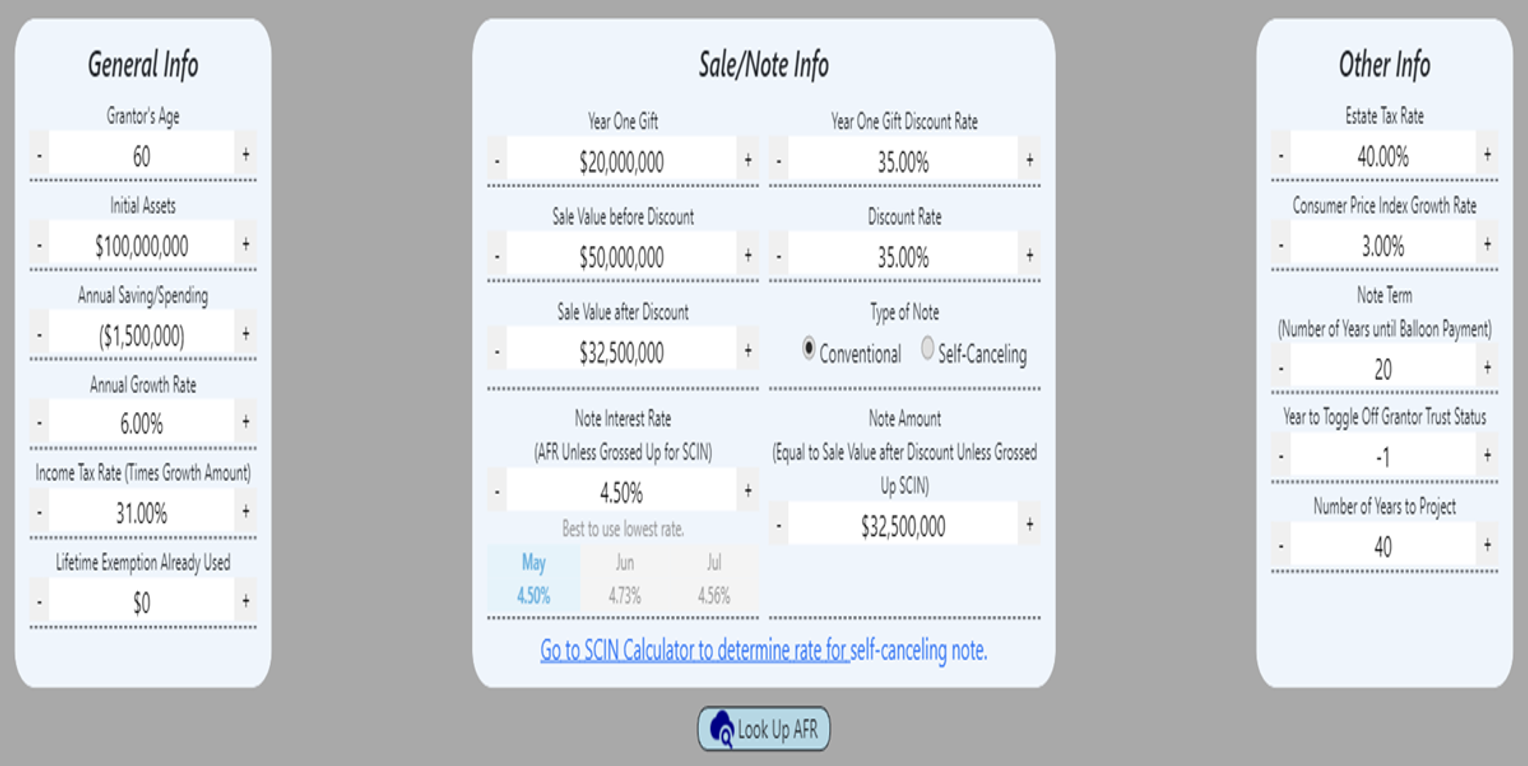

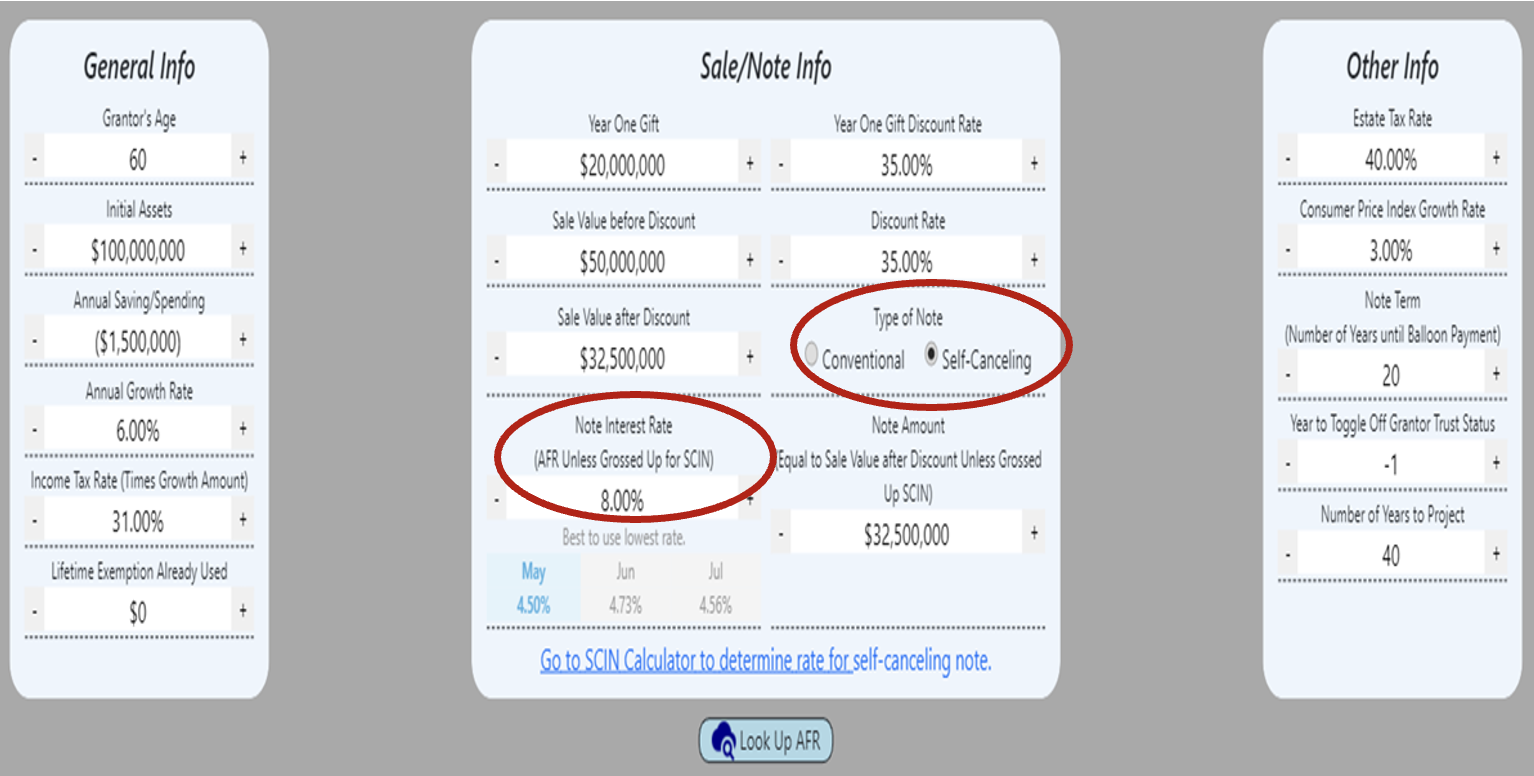

1. Assumptions

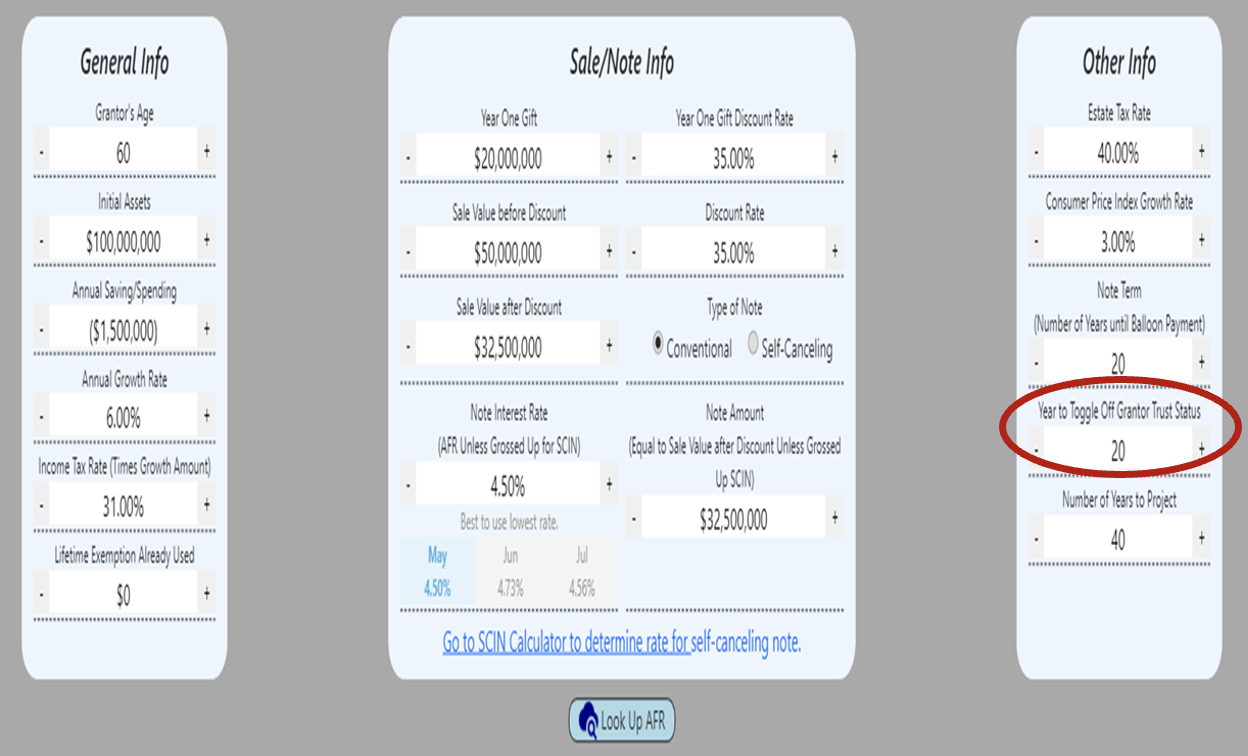

Senior, age 60, has $100,000,000 of income producing assets in an LLC, and needs $1,500,000 this year for personal consumption after social security and pension payments. Assume Senior’s living expenses increase at a 3% annual rate.

Senior transfers $70,000,000 to an LLC and assume a 35% valuation discount applies to the LLC membership interests.

Senior gifts a 28.57% membership interest in the LLC with a $20,000,000 capital account to a grantor trust as a seed gift. Applying a valuation discount, the gift of a 28.57% interest uses $13,000,000 of Senior’s $13,990,000 gift tax exemption for 2025.

Additionally, Senior sells the remaining 71.43% membership interest with a $50,000,000 capital account to the grantor trust in exchange for a $32,500,000 (assumes a 35% discount applies) 20-year, interest only promissory note bearing interest at 4.50% ($1,462,500 annual interest).

Senior retains $30,000,000 of income producing assets.

Assume a 6% investment rate of return on the $100,000,000 of income producing assets, and a 31% effective Federal and state income tax rate on capital gains and ordinary income.

After the gift and sale, the capital accounts of the LLC will be as follows:

| Capital Accounts | Capital Account Value | Discounted Value of non-voting membership interest | |

| Trust by gift (28.57% interest) | $20,000,000 | $13,000,000 (after discount) | |

| Trust by purchase (71.43% interest) | $50,000,000 | $32,500,000 (after discount) | |

| Total | $70,000,000 | ||

A summary of the transaction is shown below:

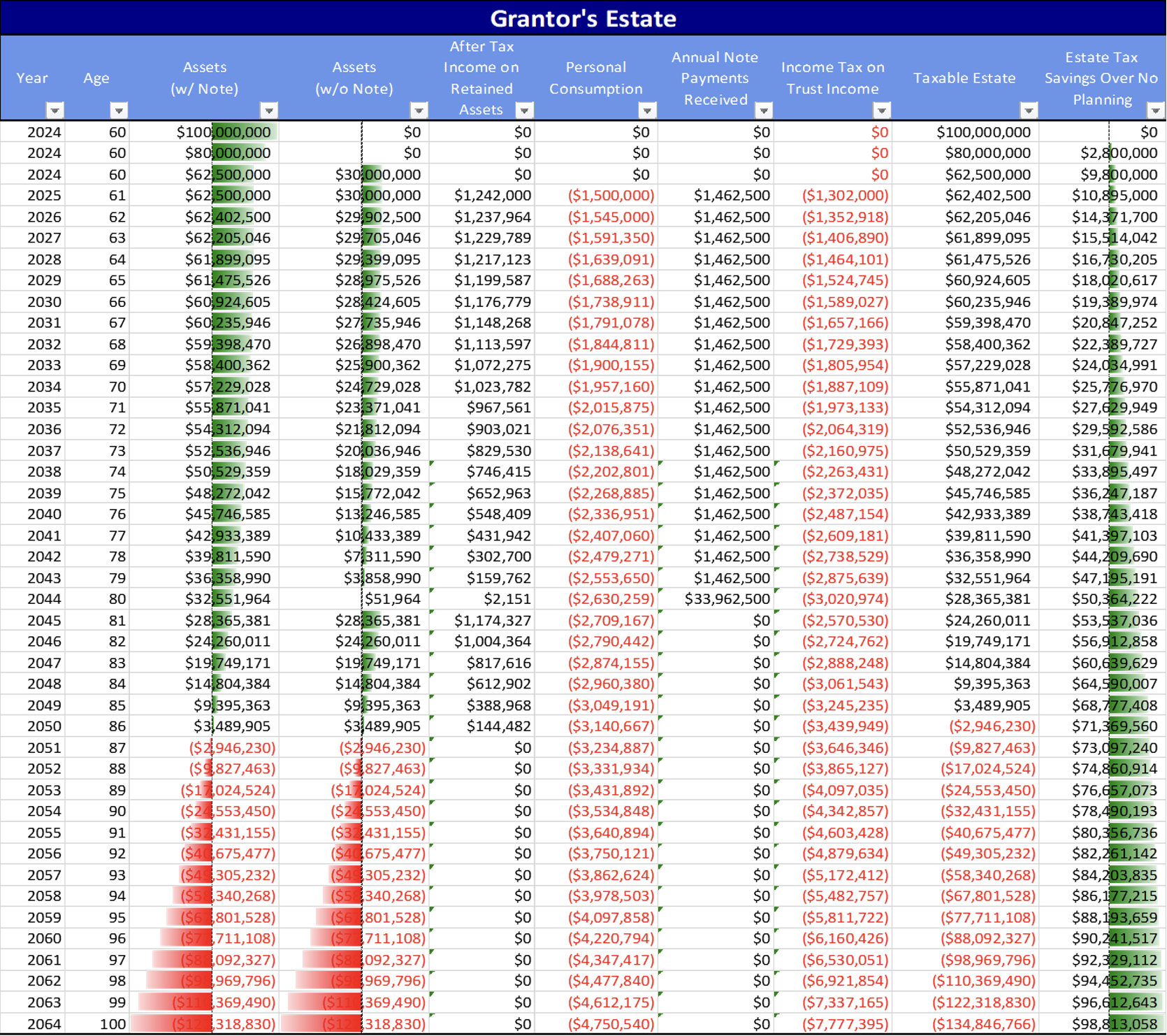

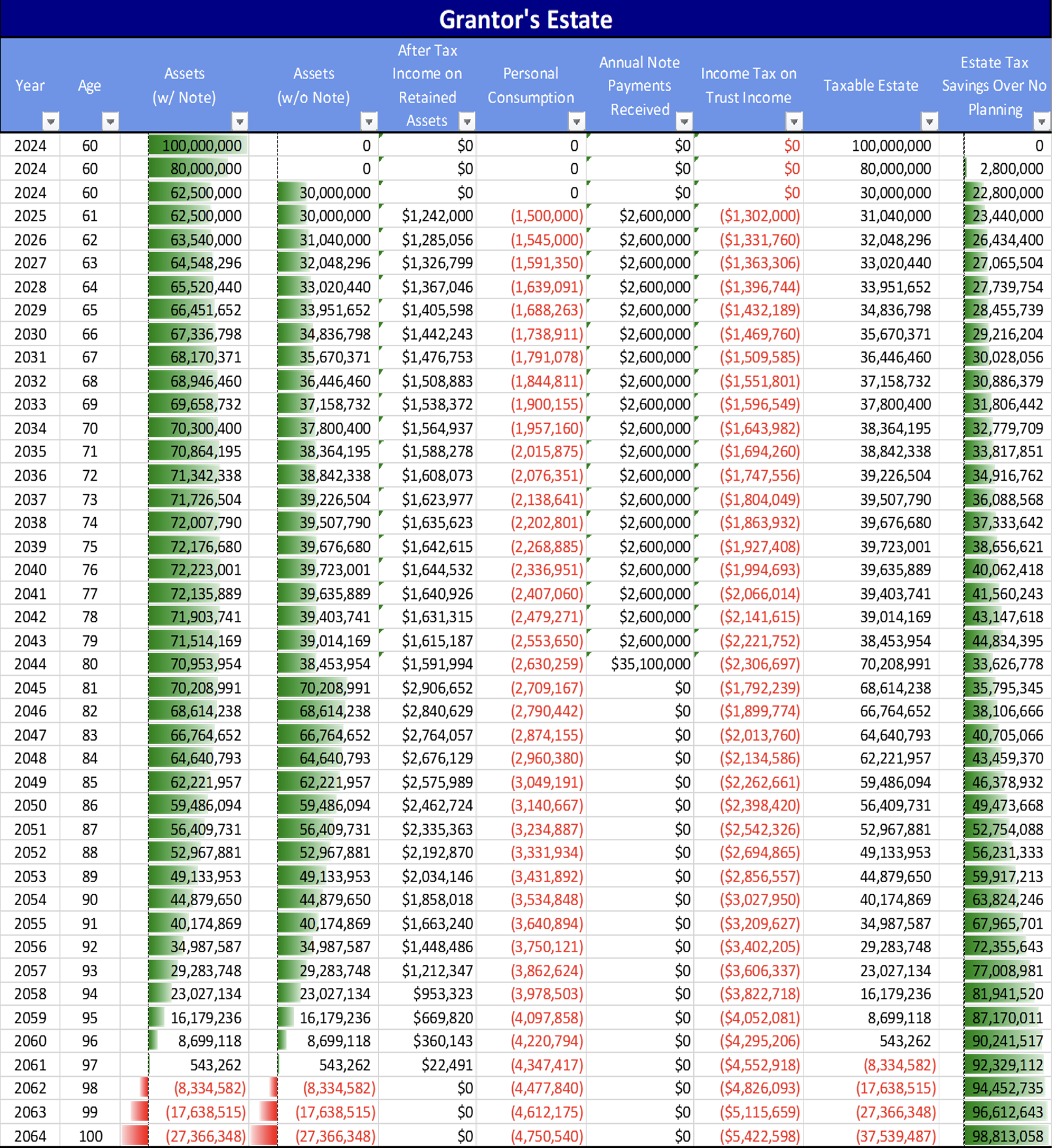

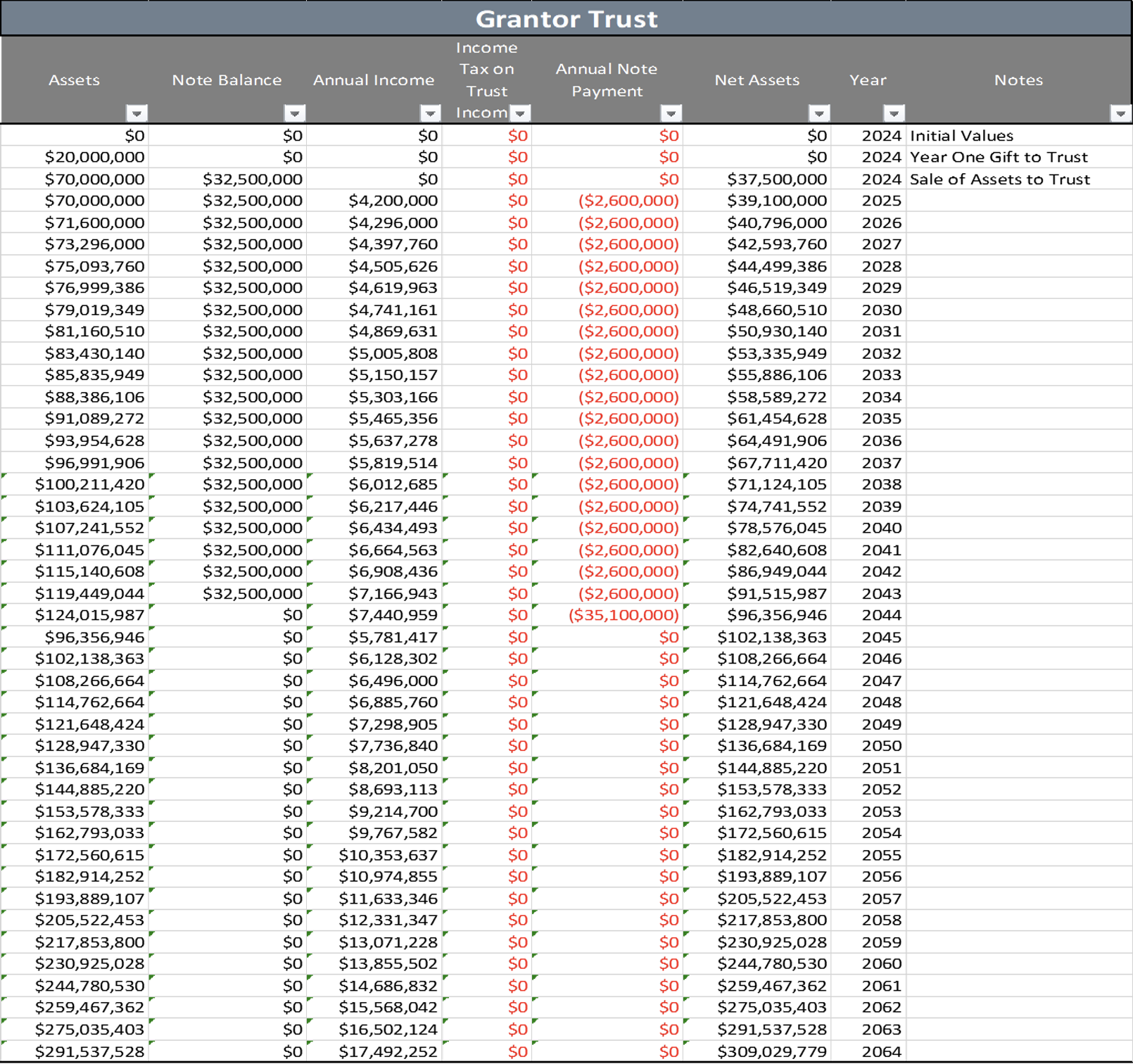

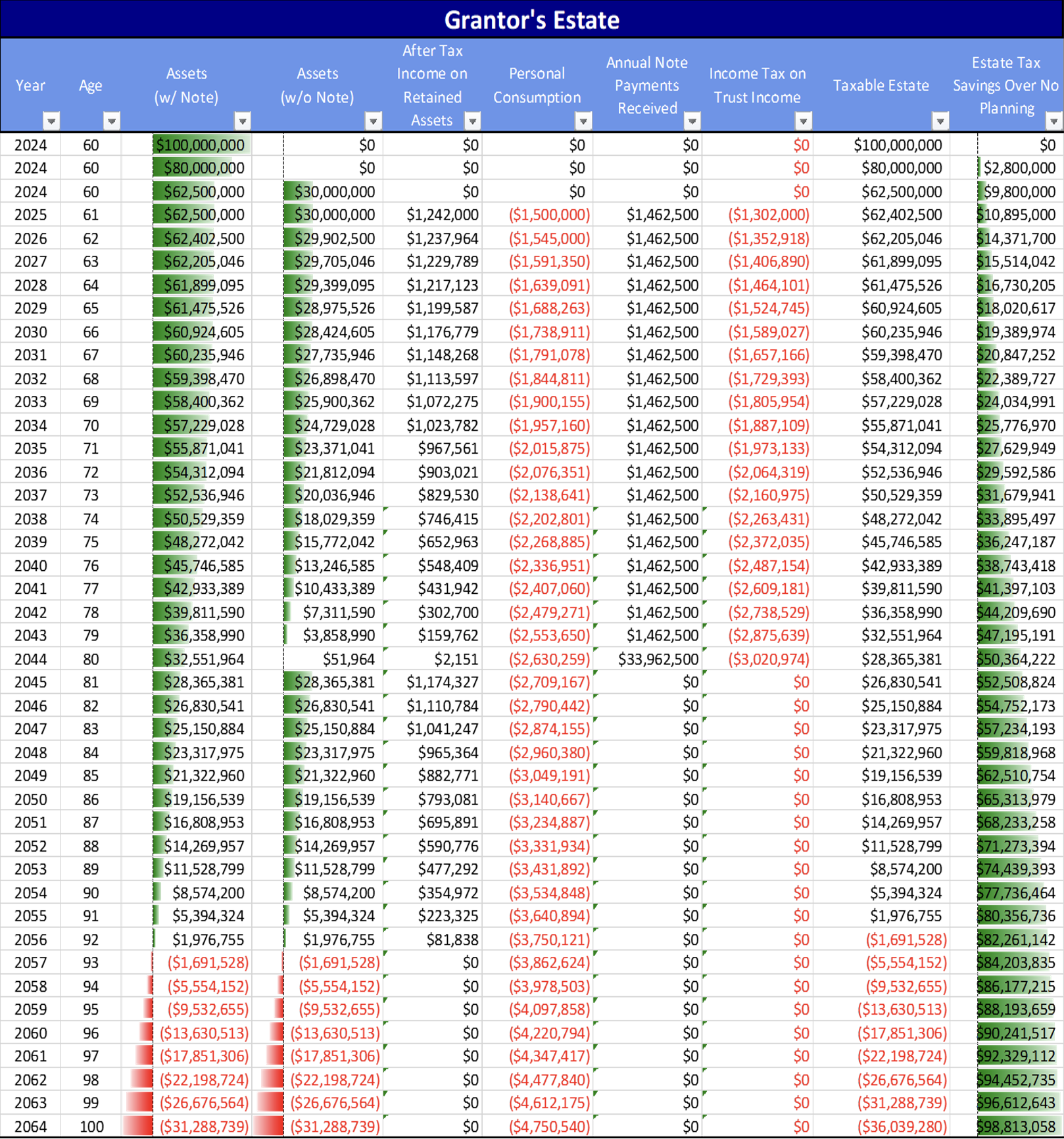

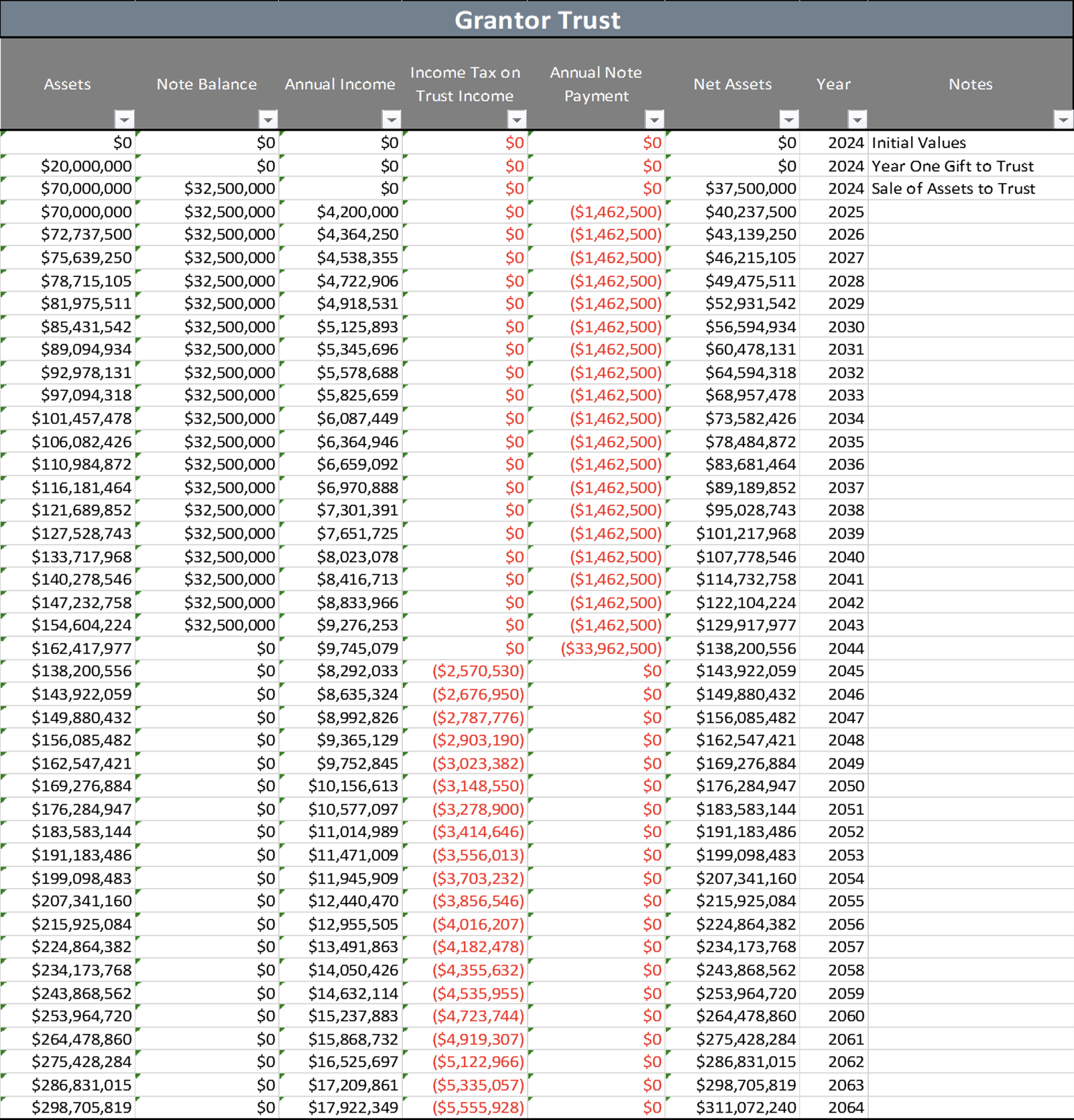

2. Financial Analysis

In the first year the income on the $30,000,000 of retained assets is $1,800,000. At a 31% income tax rate, the income taxes are $558,000, and as a result Senior nets $1,242,000 after taxes.

Senior receives $1,462,500 as an interest payment on the note that is not taxable income, and spends $1,500,000 on personal consumption.

Senior must also pay $1,302,000 of income taxes on the trust’s $4,200,000 of taxable income.

Senior must invade the principal in the first year as the revenue that Senior receives in the first year is less than the expenses for the first year.

Personal consumption and the combined income taxes during the first year depletes Senior’s retained assets by $97,500.

In the next year, with the depletion of the retained assets, the income decreased. This continues to occur throughout the life of the trust and further depletes Senior’s retained assets until all of Senior’s assets are depleted, which occurs when Senior reaches the age of 86. Another perfect estate plan if Senior dies before the age of 86!

So, what can be done to fine tune the above situation enabling Senior to live comfortably well past the age of 85?

- As the preceding examples illustrate, over an extended period the most significant wealth-shifting factor is the grantor’s obligation to pay the income taxes on a grantor trust’s taxable income. Because of the compounding benefit over a long period, the size of the income-producing assets owned by the grantor trust continue to grow. For clients with a shorter life expectancy, the impact of the compounding is less significant and can be used to determine the size of the income-producing assets the grantor needs to retain.

Although each of the following examples illustrate a single change to one element of the plan, the use of financial modeling permits one to use a combination of these mitigating factors.

V. What Can Be Done to Reduce the Grantor Trust Burn?

A. Tax reimbursement clauses.

Tax reimbursement clauses that authorize a Trustee to reimburse the grantor of a trust for income taxes the grantor pays on behalf of the Trust can be useful, but care must be taken.

The IRS approved the use of tax reimbursement clauses in Revenue Ruling 2004-64, and ruled that a tax reimbursement clause would not have the effect of including the trust in the grantor’s estate due to a retained interest in situations where the tax reimbursement was distributed pursuant to the exercise of the trustee’s discretionary authority granted under the terms of the Trust instrument. In addition, there could be no understanding, either express or implied, between the trustee and the grantor that the Trustee would reimburse the grantor.

The occasional use of this authority to reimburse the grantor may be permissible, but a continuing reimbursement of the grantor for taxes starts to look like an implied agreement between the trustee and the grantor.

In addition, unless the trust was originally drafted to include a tax reimbursement clause, the addition of a tax reimbursement clause through court reformation or otherwise with the consent of the beneficiaries of the trust may be considered to be a taxable gift by the beneficiaries back to the grantor under a recent Chief Counsel Advisory Opinion (CCA 202352018). A gift by the beneficiaries also applies in this situation where beneficiaries fail to object to a reformation of change to add a tax reimbursement clause when such beneficiaries receive notice and have a right to object to the modification.

If the beneficiaries are considered to have contributed to the trust, then it will no longer be considered to be a wholly disregarded grantor trust, and will instead be treated to some extent as a complex trust, which complicates the situation and causes some income to be taxed at the highest bracket if the complex trust portion has more than approximately $13,000 of undistributed income.

B. Terminate grantor trust treatment for the trust after the note is paid in full.

Grantor trust status may also be terminated at a certain point in time, so long as the trust’s terms do not contain powers that would not permit the trust to be considered a non-grantor trust, to allow for the trust to pay for its own income taxes.

There could be certain situations where it may not be possible to turn off grantor trust status, such as in situations where the spouse is a Trustee of the trust, or if the spouse is a beneficiary of the trust and may receive distributions without the consent of an adverse party. Knowing the financial analysis ahead of time can allow planners to appropriately draft the trust so that grantor trust can be turned off if necessary.

There are many ways that grantor trust status can be turned off, such as having the grantor release a swap power, or by giving the trustee the power to eliminate the swap power. There is the potential fiduciary concern for a trustee holding this ability, as the trustee may not be willing to turn off grantor trust status since their duty is owed to the beneficiaries of the trust, and the trustee may be concerned that turning off grantor trust status would potentially breach their duty of loyalty to only the beneficiaries of the trust. Another option may be to draft so that grantor trust status is automatically turned off at a certain point in time in the Trust Agreement to eliminate this fiduciary concern.

Trust Protectors are commonly appointed under grantor trusts and given the authority to make changes to eliminate grantor trust status, or to cause a complex trust to become a grantor trust. Trust Protector provisions must be drafted carefully to inadvertently avoid a complex trust being treated as a grantor trust.

It is important to note that grantor trust status should not be turned off while there is a note outstanding between the trust and the grantor as this could trigger income taxes on the note obligation between the grantor and the trust as if the assets would sold in exchange for the note in a fully recognized transaction.

One strategy would be to leave assets equal in value to the amount of any note or notes owed by the trust, in addition to excess value equal to approximately one-tenth of the amount owed on the note, with assets exceeding that sum being decanted into a separate trust that may be a complex trust or may be treated as owned by one or more of the beneficiaries of the trust using Internal Revenue Code Section 678.

For example, if the note owed is $900,000 and the trust has $1,600,000, then the Trustee would reserve $1,000,000 of assets in the grantor trust and transfer $600,000 of assets by decanting into a separate trust that would not be treated as owned by the grantor for federal estate tax purposes.

C. Increase the interest rate on the note by up to 5% above the Applicable Federal Rate

The Applicable Federal Rate (AFR) is the minimum rate of interest that needs to be charged to avoid an extension of credit being considered a gift for estate and gift tax purposes, but there is no prohibition in the Internal Revenue Code from charging a higher interest rate. In fact, Internal Revenue Code Section 163(j) provides that the IRS must respect an interest rate that is no greater than 5% above the AFR at the time a note is given.

Normally, the note given will bear interest at the AFR to keep the grantor’s estate as low as possible. Once the note interest rate is set it is not easy for the interest rate to be increased because this can be seen as a breach of fiduciary duty by the Trustee of a trust that voluntarily agrees to have the interest rate increase.

One potential strategy would be to have the note be a shorter term than would normally be used. While the grantor may have a 25 year life expectancy, perhaps a 9 or 12 year note may be used instead of a 25 year note, and in 9, 10 or 12 years when the note matures it could be renegotiated to up to 5% above whatever the AFR will be.

The cumulative average of the long term AFR (used for notes with a term of more than nine years) since the inception of publishing AFRs in January of 1984 is roughly 5.34%. It would therefore seem that there would be a 50% or better chance that an interest rate of up to 5.34% could be charged upon renewal.

Another possible alternative would be that the Trustee would prepay some or all of the indebtedness in a particular year, and then the grantor may loan money to the trust in a later year by independent action that would hopefully not be characterized as an increase in the interest rate owed on the loan to be repaid.

It is also worthwhile to consider the use of a Self-Cancelling Installment Note which carries a higher interest rate to cover the risk premium that the note may not be repaid if the grantor dies during the note term. It would seem acceptable to convert a conventional Non-Self-Cancelling Installment Note into a Self-Cancelling Installment Note in exchange for a higher interest rate and consequently higher payments to the grantor.

D. Invest some of the trust’s assets in municipal bonds or assets that appreciate and that will not be sold while the grantor is living.

Changing the investment mix of the grantor trust assets to non-taxable municipal bonds or long-term growth stocks, or other assets that appreciate in value that will not be sold may also be a strategy to reduce the Grantor Trust Burn. Since the assets would produce limited taxable income until sold the Grantor has a lower tax burden and may retain additional assets.

E. Invest trust assets in high cash value, low death benefit life insurance using conventional products or individually customized Private Placement Life Insurance (“PPLI”).

By the time the burn is noticed by the grantor, or the grantor’s financial advisors, the trust is likely producing a significant amount of income. Instead of reinvesting that income in the assets that continue to produce sizeable income tax liability issues for the grantor, the trustee could use some of the trust’s assets to invest in certain types of life insurance. Instead of utilizing Crummey powers, which can require use of the grantor’s GST-exemption, to pay for the policy’s premiums, the trustee could use the trust assets to purchase life insurance on the grantor’s life, or a joint life policy on the grantor and grantor’s spouse.

If the goal is to eliminate some of the income tax liability that ultimately flows to the grantor’s personal income tax return, it may be beneficial to invest in a variable universal life policy or private placement life insurance (PPLI). Both of these types of insurance strategies allow for a large investment that immediately builds cash value, which can then be used to invest that cash value in a broad array of assets, including inefficient tax assets like hedge funds and private equity, without being subject to income tax. In addition, if ever necessary, loans and withdrawals of the cash value without being subject to income tax may be possible.[1]Finally, the policy death benefits are not subject to income tax, estate, and potentially GST-tax, as well. Because variable policies, including PPLI, often require significant premiums to be paid in the early policy years, these structures may be a great choice to mitigate the burn by taking assets and purchasing a variable policy rather than continuing to invest those dollars in other assets that will produce income over time. Instead, the assets will be used to purchase assets inside an insurance wrapper that can be invested without causing additional income tax liabilities on those assets, which will ultimately slow the burn for the grantor.

F. Distribute some of the trust’s income producing assets to the beneficiaries.

G. Use a private annuity sale to continue payments to the Grantor for life.

Alternatively, the grantor could sell assets to the grantor trust in exchange for a promise from the grantor trust to make annual payments back to the grantor or grantor and spouse for life. One big benefit is that the amount transferred in exchange for the private annuity is removed from the grantor’s/annuitant’s gross estate, unlike the installment sale transaction, which only removes a portion of the appreciation from the grantor’s estate. At the grantor’s death, the annuity obligation terminates, and like a SCIN, nothing is included in the grantor’s gross estate. Important to note, variable annuity contracts can also be used to defer income recognition but will result in ordinary income being recognized upon withdrawal to the extent of appreciation within the contract. The use of private annuities is discussed in more detail in Section VI below.

H. Invest trust assets in encumbered real estate to shelter taxable income with depreciation losses, such as bonus depreciation.

A trustee should be chosen who understands the grantor’s perils regarding the income tax burn, because the trustee can then work with an investment professional to determine what kinds of assets and strategies in which to invest. For example, as part of the trust’s investment portfolio, the trustee may determine a need for real assets as part of a diversification strategy. Investing in certain types of real estate may allow the grantor to depreciate the real estate investment and immediately lower the grantor’s income tax liability. In addition, cost segregation or bonus depreciation allowances may allow the grantor to speed up the depreciation schedule, thereby increasing the amount the grantor may deduct against other tax liabilities in large income recognition years.

There may also be other tax credits, such as the energy tax credits newly allowed under the Inflation Reduction Act, which could help offset some of the trust’s or grantor’s income. The trustee should consult with their own and the grantor’s financial and tax advisors to maximize the benefits of tax lost harvesting across the two portfolios, since they are treated as a single portfolio from an income tax perspective.

I. If Senior were married a SLAT could be used so that trust distributions can be made to the grantor’s spouse, but this is only viable if the grantor’s spouse does not predecease the grantor.

One straightforward way to mitigate the burn is to include a spouse as a permissible beneficiary of the trust.[2] The trustee could then distribute some of the trust’s assets to the spousal beneficiary, who could then use the distribution to cover expenses or income taxes, assuming that the grantor and the grantor’s spouse file joint tax returns. If the grantor is currently unmarried, a trust protector could be given the power to add the grantor’s spouse as a permissible beneficiary at some point in the future.

There are two potential pitfalls to this straightforward solution. First, there are the common risks associated with all SLATs – that the spousal beneficiary predeceases the grantor or a divorce between the spouses occurs. The death of the spousal beneficiary before the grantor or a divorce between spouses could be disastrous to any plan to mitigate the burn by making a distribution to the spouse. Divorce creates further problems, since section 677 relies on section 672(e) for determining whether a spouse’s interests is attributable to the grantor, and section 672 looks to whether the grantor and the grantor’s spouse were married at the time of the creation of the trust, which effectively eliminates the ability for divorced spouses to toggle grantor trust status off. Of course, this mortality risk can itself be mitigated by taking out life insurance on the spousal beneficiary or by having nonreciprocal trusts. One might also consider drafting the trust so that the spouse may only receive distributions with the consent of an adverse party (e.g., another trust beneficiary) so that it is possible to turn off grantor trust status in the future.

Moreover, if the trustee makes a distribution to the spousal beneficiary each year in the amount of the income taxes due on the trust’s behalf, this could be seen as an implied agreement between the grantor and the trustee to reimburse the grantor for income taxes paid, triggering the harsh consequences of gross estate inclusion under Rev. Rul. 2004-64. In addition, potential claims could be made that the trustee is violating its fiduciary duties towards the beneficiaries by distribution estate tax-free and often GST tax-free assets to the spousal beneficiary.

J. Give the independent trustee the discretionary power to add the grantor as a beneficiary in a state like Nevada that has legislation that the grantor’s creditors cannot go after trust assets.

If the grantor could retain access to the trust’s assets by creating a self-settled trust – or a trust that gives the trustee the power to make distributions to the grantor – concerns over the burn of grantor trust status would quickly dissipate. The power of a trustee to make distributions from a trust to its grantor should not, by itself, cause the transfer to the trust to be an incomplete gift for gift tax purposes.[3] This should not, by itself, cause the trust property to be included in the grantor’s gross estate under section 2036, even if the grantor actually receives distributions.[4] Instead, the issue that arises is that if the grantor’s creditors can compel the trustee to use trust property to pay the grantor’s debts, the transfer will likely be incomplete and will expose the trust assets to the grantor’s gross estate under sections 2036 and 2038.[5] It is the potential exposure to the grantor’s creditors that creates incomplete gift and estate inclusion issues.

Despite that the Uniform Trust Code, adopted in most states, provides that creditors can reach the assets of a self-settled trust,[6] a number of other states have statues that permit grantors to create self-settled trusts in certain circumstances without exposing the trust assets to the claims of the grantor’s creditors. Trusts established in these states are often referred to as domestic asset protection trusts, or DAPTs. If the grantor is a resident of one of the handful of states that allow DAPTs[7], then the grantor’s gifts to the trust should be complete, and the trust assets should not be included in the grantor’s gross estate under sections 2036 or 2038.[8] For grantors who are not residents of states with DAPT statutes, the outcome is less clear because of conflict of law issues. To account for this, some avoid naming the grantor as a beneficiary of the trust at the outset and instead include a provision that permits another person to add the grantor as a beneficiary at some point. These arrangements – often referred to as hybrid DAPTs – do not definitively prevent a court from subjecting the trust’s assets to the claims of the grantor’s creditors, however it would seem that the risk of estate inclusion would be significantly reduced particularly if the grantor could only be added back in as a beneficiary of the trust upon the occurrence of an act of independent significance such as if the grantor’s net worth is below a certain threshold, or there is a divorce situation.[9]

A similar, but potentially more certain, arrangement to provide the grantor with access to the trust to ameliorate the burn is a special power of appointment trust or SPAT. A SPAT is an irrevocable trust created for beneficiaries other than the grantor, in which one or more individuals, (other than the grantor) have a lifetime special power of appointment, held in a nonfiduciary capacity, that may be used to direct assets back to or for the benefit of the grantor.[10] Because the grantor is not a beneficiary of the trust, this kind of trust may sidestep concerns over it being self-settled and thereby eliminate creditor issues, as well. However, because certain states might argue that the trust should be treated as a self-settled trust, it may be beneficial to locate the trust in a DAPT state and create the necessary nexus to that state.

K. Prepay the note in whole or in part before maturity date.

The main purpose of an installment sale transaction is to lend assets to a trust, so that any income and appreciation those assets earn, or return inures to the benefit of the trust. The longer the trust holds assets, the more income and appreciation it will have. This in turn will continue to increase and compound the grantor’s income tax payments due on the trust’s assets, causing his “burn” to worsen. If the borrowed funds are returned to the grantor early, any future income and appreciation will revert to the benefit of the grantor, putting additional assets back into the grantor’s hands that can be used to cover taxes and living expenses.

L. Use a Self-Cancelling Installment Note.

In a typical sale to grantor trust transaction, the minimum AFR rate available as of the date of the transaction is used to calculate the interest payable on the note, which can be the lowest of the month of the transaction, or the prior two months preceding the month of the transaction. The use of the minimum interest rate ensures the maximum estate tax benefit for the grantor, since grantors are typically interested in maximizing the value retained in the trust while minimizing the value distributed back to them and into their gross estate. However, these interest payments can often be used to help mitigate the burn over time. Indeed, in our example above, the $1,462,500 received each year by the grantor from the trust in the form of interest payments helps stave off the ultimate depletion of the grantor’s wealth. When the note term ends, so too do the interest payments. This is partially offset, of course, by the large balloon principal payment, but as we’ve seen, that principal is quickly depleted as the trust assets continue to grow and compound over time.

There may be a couple of interesting solutions here to increase the interest payments on the note by refinancing it. First, if the AFR rate has risen, as they indeed have precipitously over the last couple of years, it may behoove the grantor to consider refinancing the note with the higher AFR rate, so that the trust must increase the interest payments back to the grantor. Increasing the AFR rate from 1% to 4% on a $10 million note yields an additional $300,000 to the grantor; for a $100 million note, the interest payments increase proportionally by $3 million.

However, there is no reason that the AFR rate must have risen in order to refinance and take advantage of a higher rate. The AFR rate is the minimum amount of interest that can be charted on an intra-family loan without the risk of a taxable transfer. As of the date of finalization of this paper, the long-term AFR rate as, compounded semiannually in April 2025 is 4.61%; there is no reason that the note written or refinanced today between a grantor and grantor trust couldn’t be greater than that minimum rate. Notably, the IRS does not set a maximum rate for private loans.[11] Thus, as the note term nears its end, or as subsequent sales are made to the grantor trust, a higher rate than the AFR can be chosen to push additional assets out of the trust and back to the grantor.

Charging a higher rate, however, may frustrate the beneficiaries, who would like to see more assets retained in the trust using the minimum rate. Therefore, the beneficiaries should get something in return for the higher rate charged. One potential for that consideration is to create a self-cancelling installment note (SCIN) that allows the debt obligation to terminate on the death of the lender-grantor. The self-cancelling feature of a SCIN provides two important benefits if the grantor dies during the note term. First, the grantor trust is relieved from future payment obligations (i.e., the remaining principal balance does not need to be paid to the grantor’s estate). Second, the outstanding principal is generally excluded from the grantor’s gross estate.[12] Under section 163(i), to compensate for the risk that the lender may die before receiving payments in full satisfaction of the amount lent, the grantor trust must pay a premium, either in the form of a higher purchase price/principal amount or a higher interest rate.[13] Therefore, increasing the interest rate on the initial note, or at refinancing, could be done such that the additional interest charged is sufficient to cover the premium to qualify for SCIN treatment.

As the original note term nears its end, the grantor and the grantor trust could refinance the note, using the higher interest rate to mitigate the burn while providing that the note is canceled upon the death of the grantor as consideration for the refinancing. The term of the note should not exceed the grantor’s life expectancy; otherwise, the note could be recharacterized as a private annuity for income tax purposes.[14] To calculate the new interest rate for the bargained cancellation feature of the note, an annuity factor for the shorter of the new term or for the grantor’s life expectancy found under section 7520 should be used. This factor should then be divided by the value of the property purchased to determine the anticipated payments needed to cause the present value of such payments equal to the value of the property purchased using the SCIN.[15]Effort should be taken to ensure that the applicable interest rate is not more than five percentage points above the AFR in effect at the time to ensure that the special rules of section 163(i) do not apply.

Typically, SCINs presents an opposite mortality risk since the tax benefits of the transaction are lost if you live longer than expected. But in situations where the goal is to mitigate the grantor’s burn, it may end up being a boon for the grantor rather than posing a risk, since the grantor will benefit from higher interest payments from the trust to cover expenses and taxes, and if the grantor dies prior to the full satisfaction of the note, everybody wins. From the perspective of fiduciary obligations, the trustee may also prefer this kind of transaction rather than just increasing the interest rate without adequate consideration, since the higher rate is given in return for the cancellation feature, which could significantly benefit the trust’s beneficiaries if the grantor dies prior to the grantor’s life expectancy.

M. Retain additional assets and consider purchasing nursing home insurance and disability insurance to help account for unforeseen circumstances.

N. Given that the discount is less significant than the burn, reduce the size of the valuation discount, which would potentially minimize the audit exposure.

VI. Examples to Illustrate the Strategies That Can Be Used to Reduce the Impact of the Grantor Trust Burn.

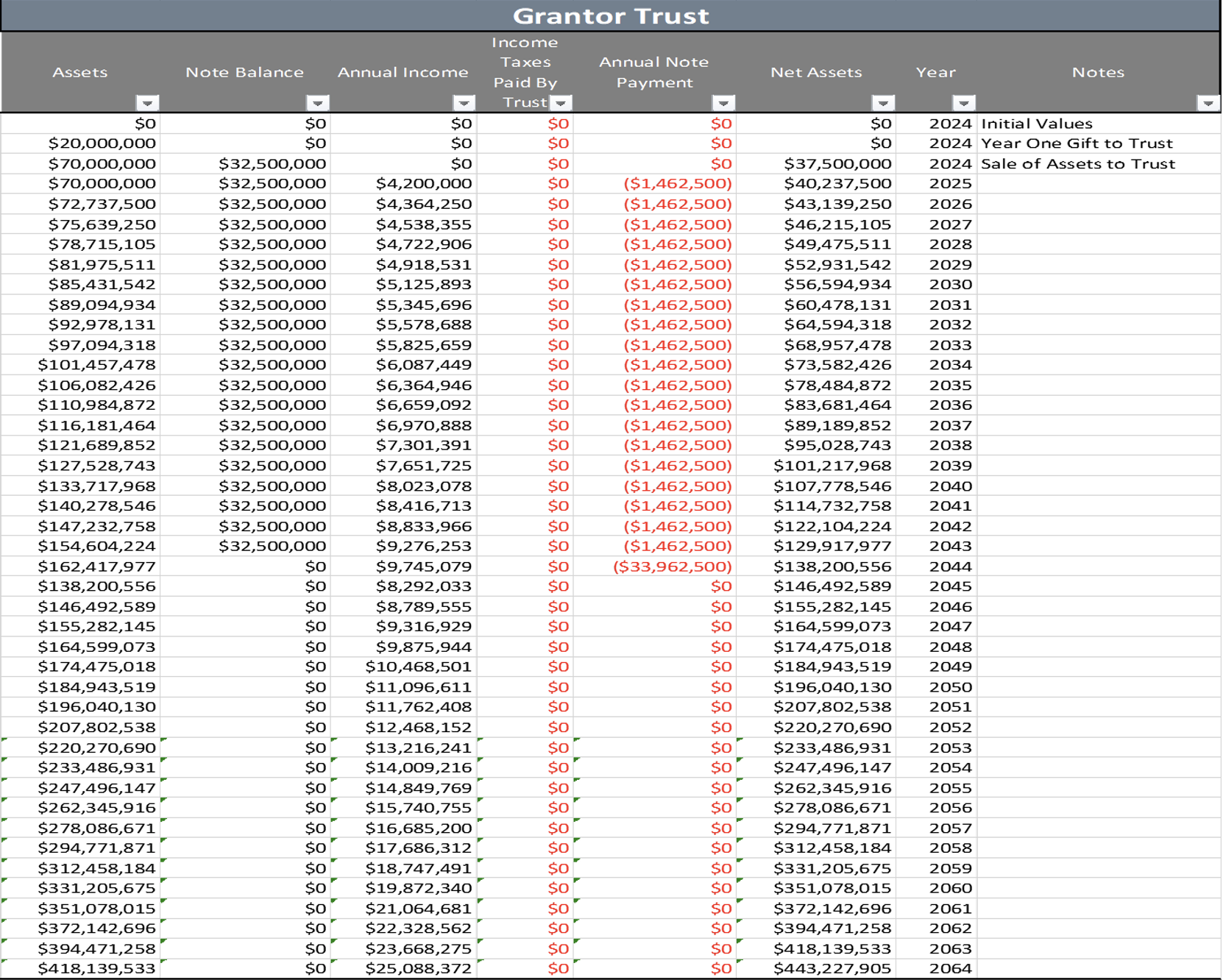

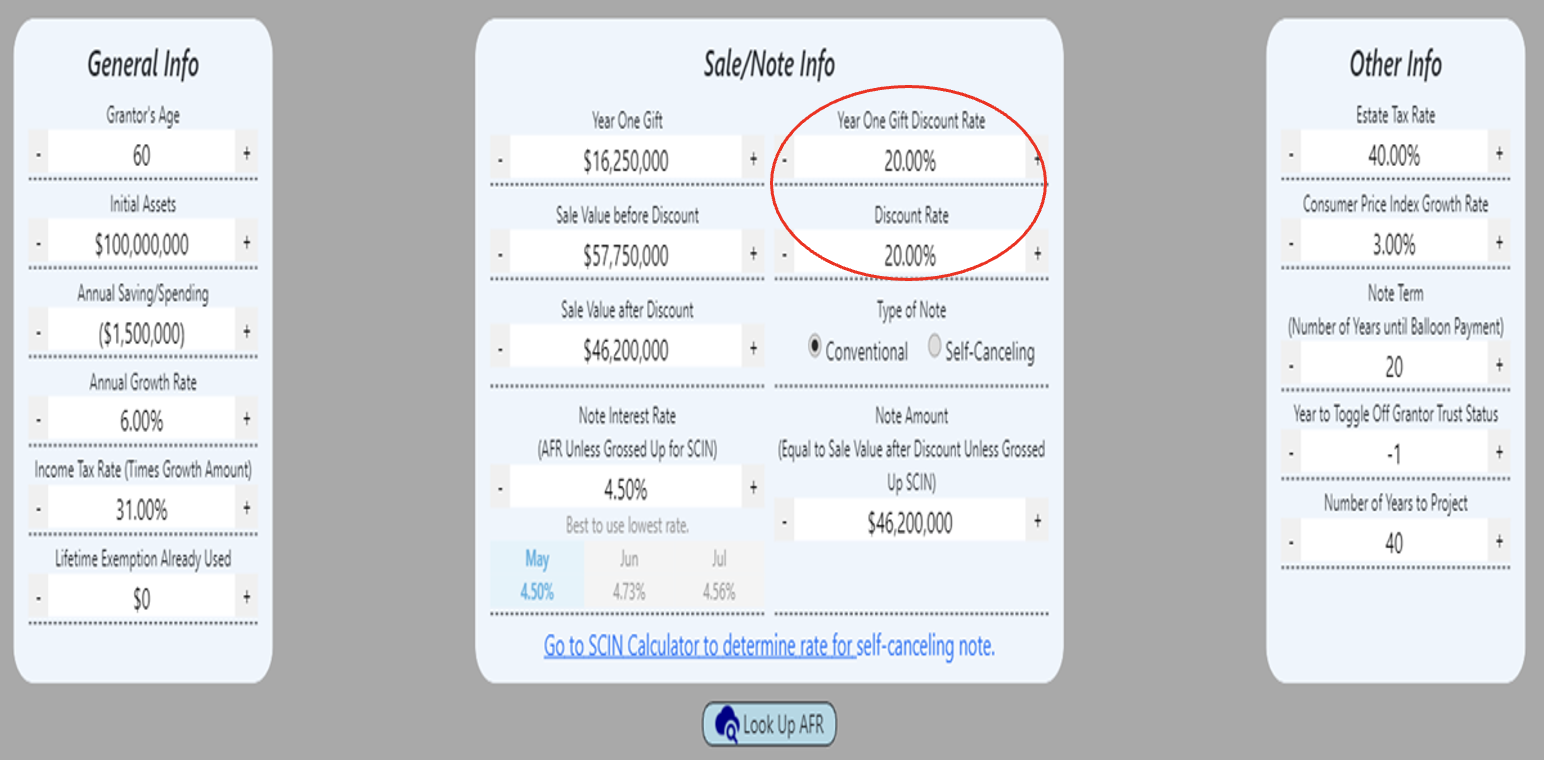

A. Alternative One – Reduce the Discount Rate to 20%

Assuming the same facts as a prior example, reducing the discount rate to 20% has a negligible impact on Senior’s retained assets. As illustrated below, the reduction of the discount rate allows Senior to retain sufficient assets to support his lifestyle to age 92, as compared to age 87 with a 35% discount.

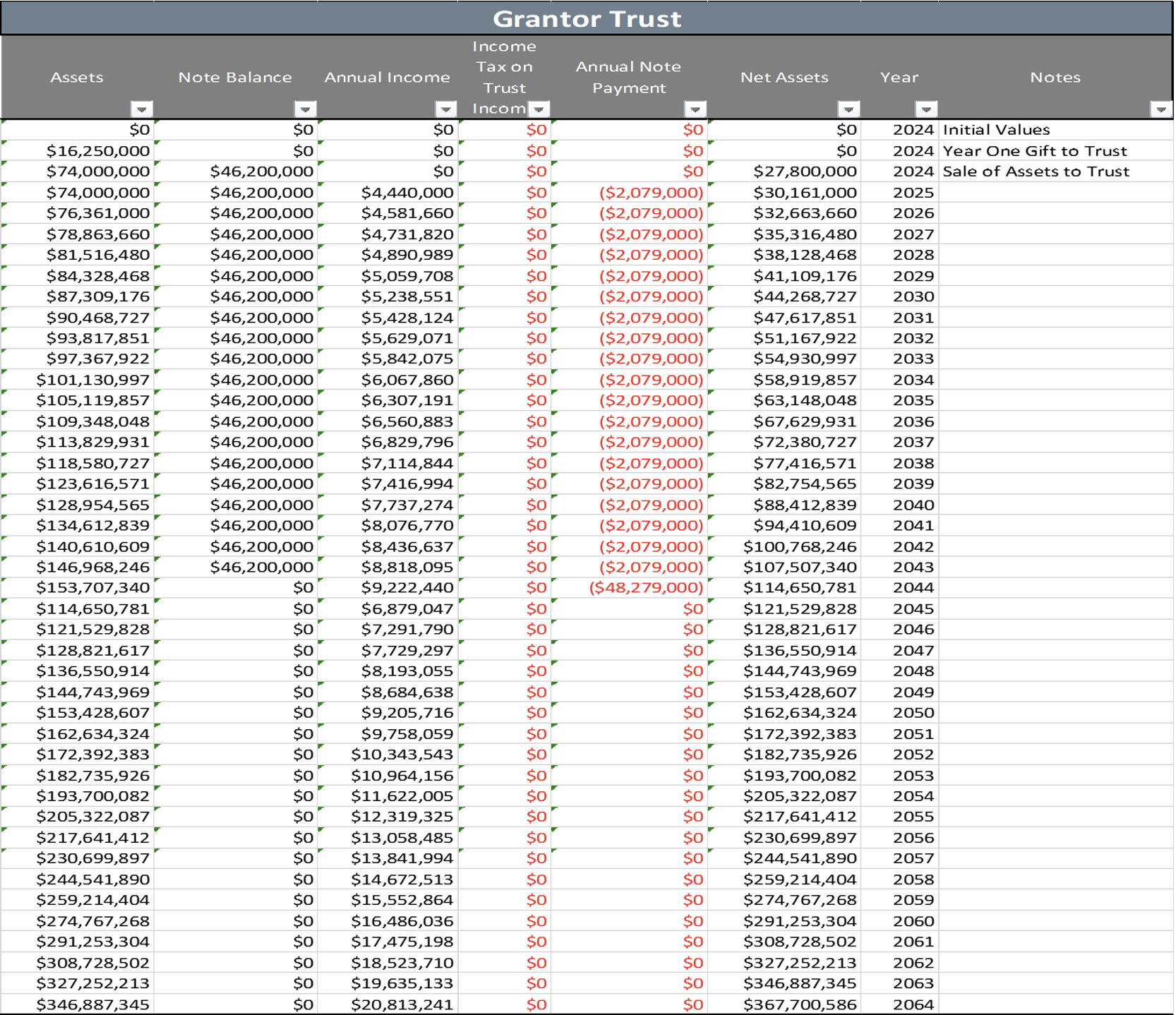

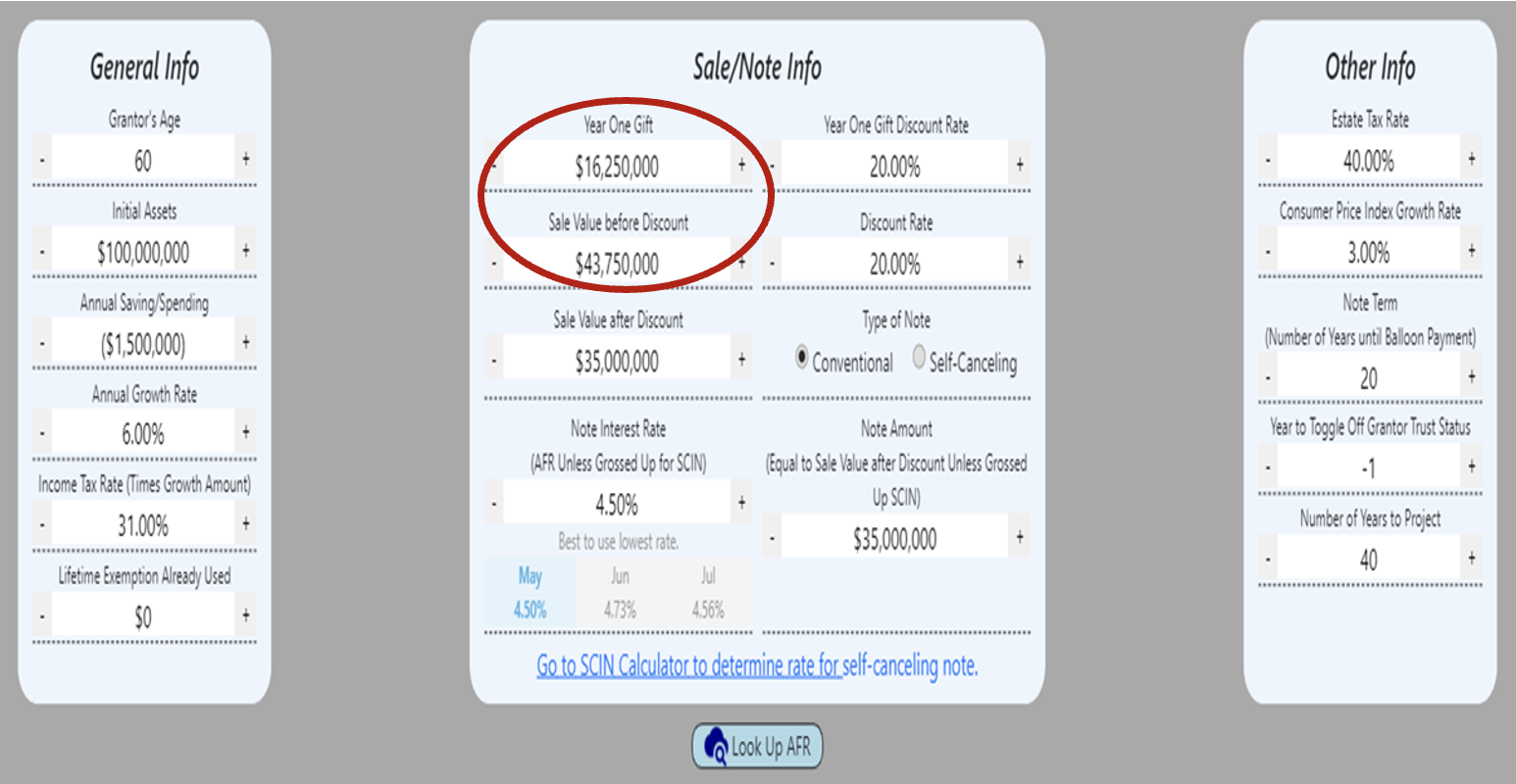

B. Alternative Two – Retain Additional Assets

Assume the same facts as the prior example, except that Senior retains $40,000,000 of income producing assets. As illustrated below, the retention of additional assets allows Senior to retain sufficient assets to support his lifestyle to age 97, as compared to age 92 in the prior example.

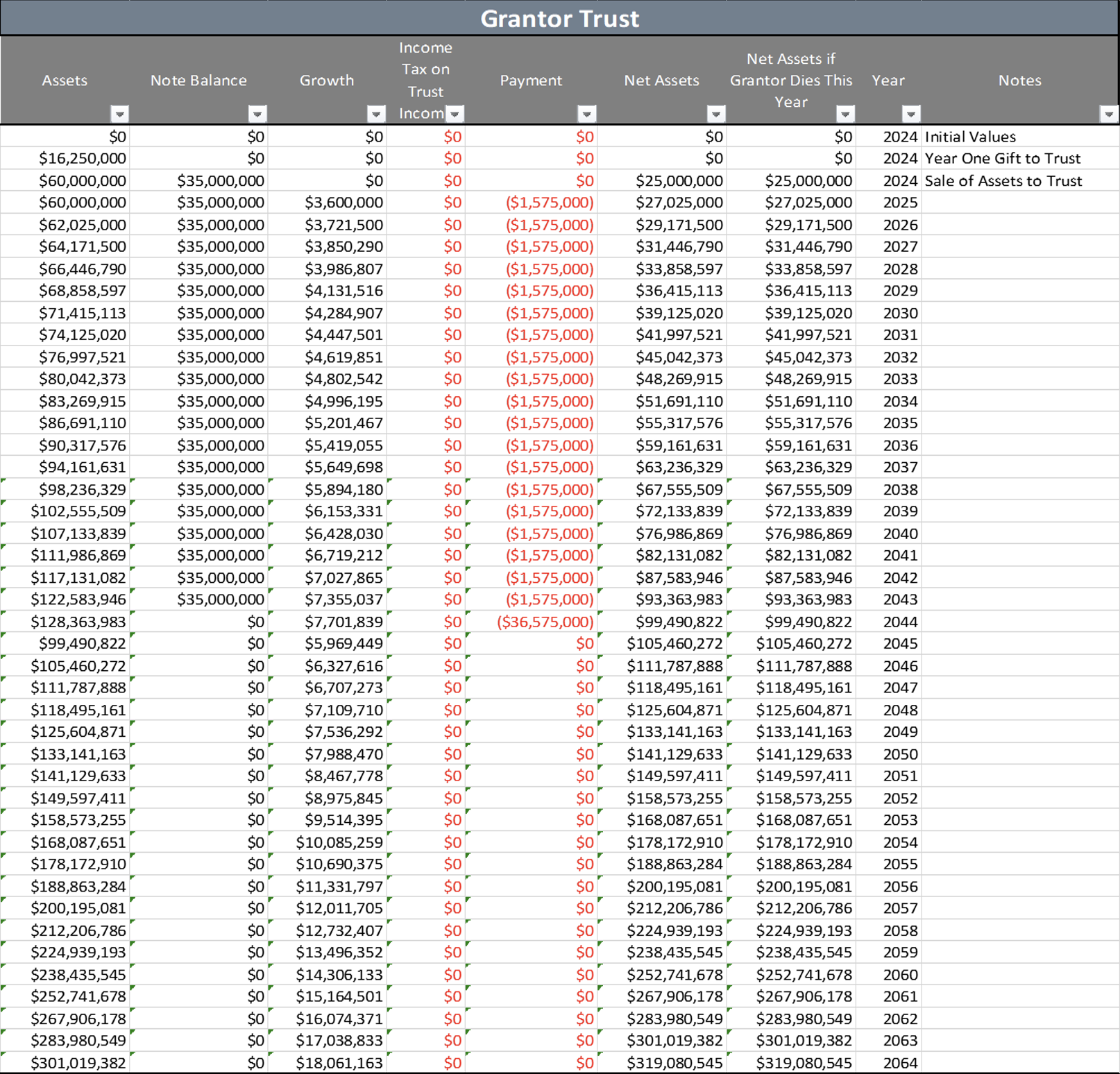

C. Alternative Three – Increase the Interest Rate to 8.0% and use a Self-Canceling Installment Note

Assume the same facts as the prior examples, except that the promissory note is a Self-Canceling Installment Note bearing interest at 8.0%. As illustrated below, the increased interest rate allows Senior to retain sufficient assets to support his lifestyle to age 97. Further, if Senior dies prior to his life expectancy the note will automatically cancel and does not have to be repaid, resulting in the note not being included in Senior’s estate.

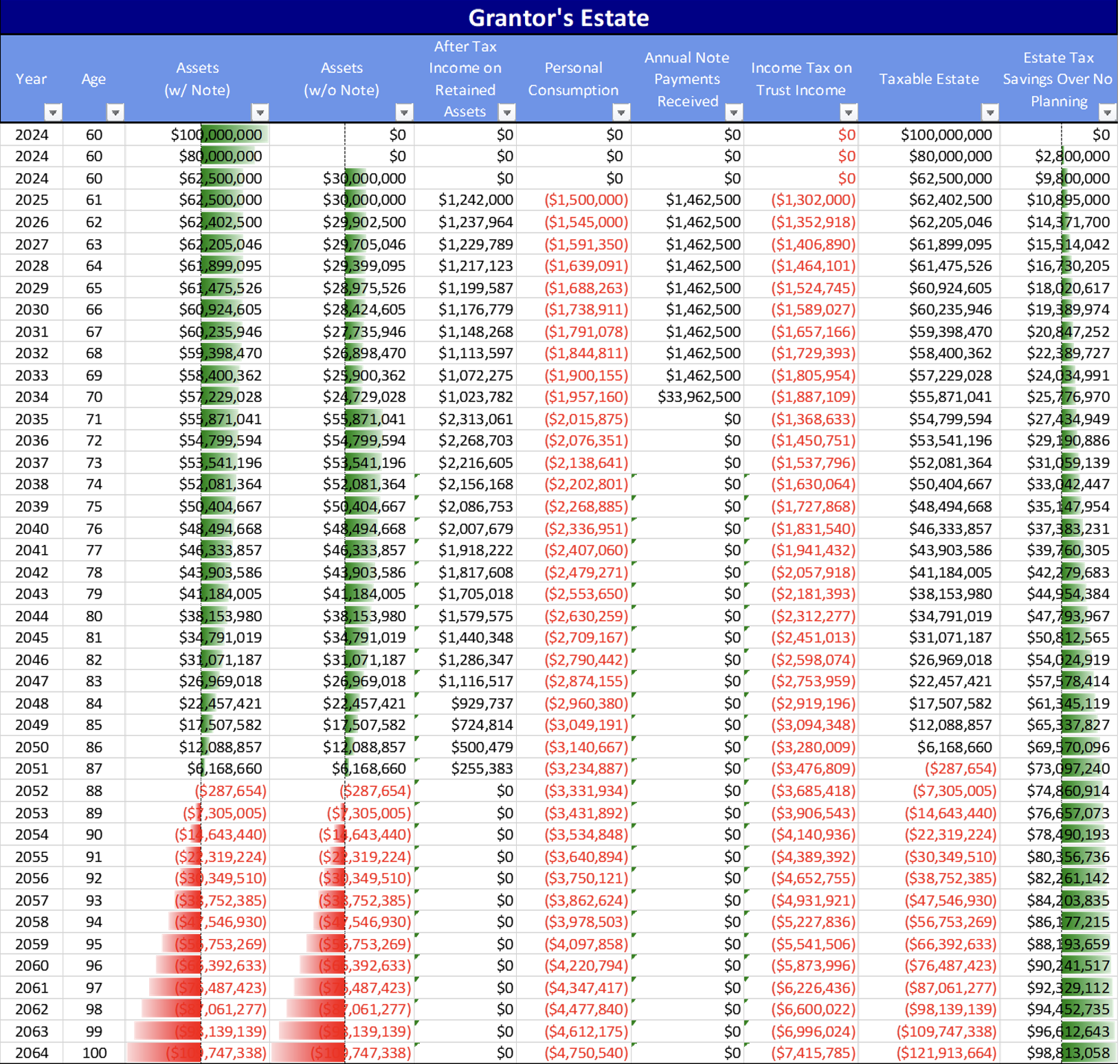

D. Alternative Four – Turn off Grantor Trust Status in Year 20 After the Note is Repaid

Assume the same facts as the prior examples, except that grantor trust status is turned off in year 20 after the promissory note is repaid. There could be adverse income tax consequences if grantor trust status is terminated prior to the note being repaid. It is possible to prepay the note if one desires to convert to a non-grantor trust after such prepayments. As illustrated below, the conversion only allows Senior to retain sufficient assets to support his lifestyle to age 92.

E. Alternative Five – Change Term of Note to Ten Years

Assume the same facts as the prior examples, except that the note is repaid in ten years instead of twenty. As illustrated below, the advance payment of the note does little to decrease the impact of the Grantor Trust Burn and only allows Senior to retain sufficient assets to support his lifestyle to age 87.

F. Valuation Adjustment Clauses

Planners should also consider what kind of valuation adjustment clause and other mechanisms should be used to help to take into consideration that the IRS may challenge discounts or take the position that there is not a bona fide business reason for a particular sale or structure. While a full discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this outline, a Grantor’s family may be much better off paying gift tax and having all of an intended gift occur at the time of a transfer, as opposed to using a “Wandry” or other “portion transferred” adjustment clause, which may cause a significant portion of the value of an asset or assets and the income and cash flow therefrom to not be held in trust for a particular family.

One consideration is whether the family would be better off using a “King Clause,” which provides that the Grantor will be owed money, based upon any difference between the value of what is transferred and the expected or agreed upon value at the time of transfer in the form of a long-term promissory note with interest at the long-term Applicable Federal Rate, so that the full value of the transfer and whatever discount is negotiated or permitted inures to the benefit of the applicable trust or other recipient of the transfer.

For example, if a 50% non-voting member interest in an LLC holding $10 million worth of assets that will grow at 7.2% per year is transferred to an irrevocable trust and valued at the time of gift at $3 million, and a valuation adjustment clause is used, which provides that any excess in value over $3 million essentially stays with the donor. If the Tax Court determines that the 50% interest is really worth $4 million so that this was a 37.5% transfer and the donor kept 12.5%, this results in no additional gift to the trust upon revaluation; however the additional 12.5% currently value at $1 million will be included in the grantor’s estate potentially causing use of an additional amount of the donor’s estate tax exemption, or creating an additional $400,000 of estate tax, if the donor does not have remaining estate tax exemption to absorb this.

If instead the valuation adjustment clause called for an increase in the promissory note amount, or an increase in the annuity amount being paid back to the grantor then the additional 12.5% would be a completed gift outside of the estate causing future appreciation to pass outside of the estate.

What are the estate tax savings of a completed gift of the 12.5% in question?

12.5% of $10 million is $1,250,000, which will double in value every 10 years assuming a 7.2% rate of return, so that in 20 years, this will be worth $5,000,000.

40% of $5,000,000 less the additional $1,000,000 of consideration provided because of the valuation adjustment clause, so $1.6 million of estate tax is saved in this example, not counting “the burn” that would occur as a result of the additional 12.5% interest being transferred.

If this were an installment sale situation, it would seem to be a “no brainer” that the donor’s family would have been better off if the donor had received back a larger promissory note bearing interest at the long-term AFR as opposed to having transferred a smaller percentage of the LLC.

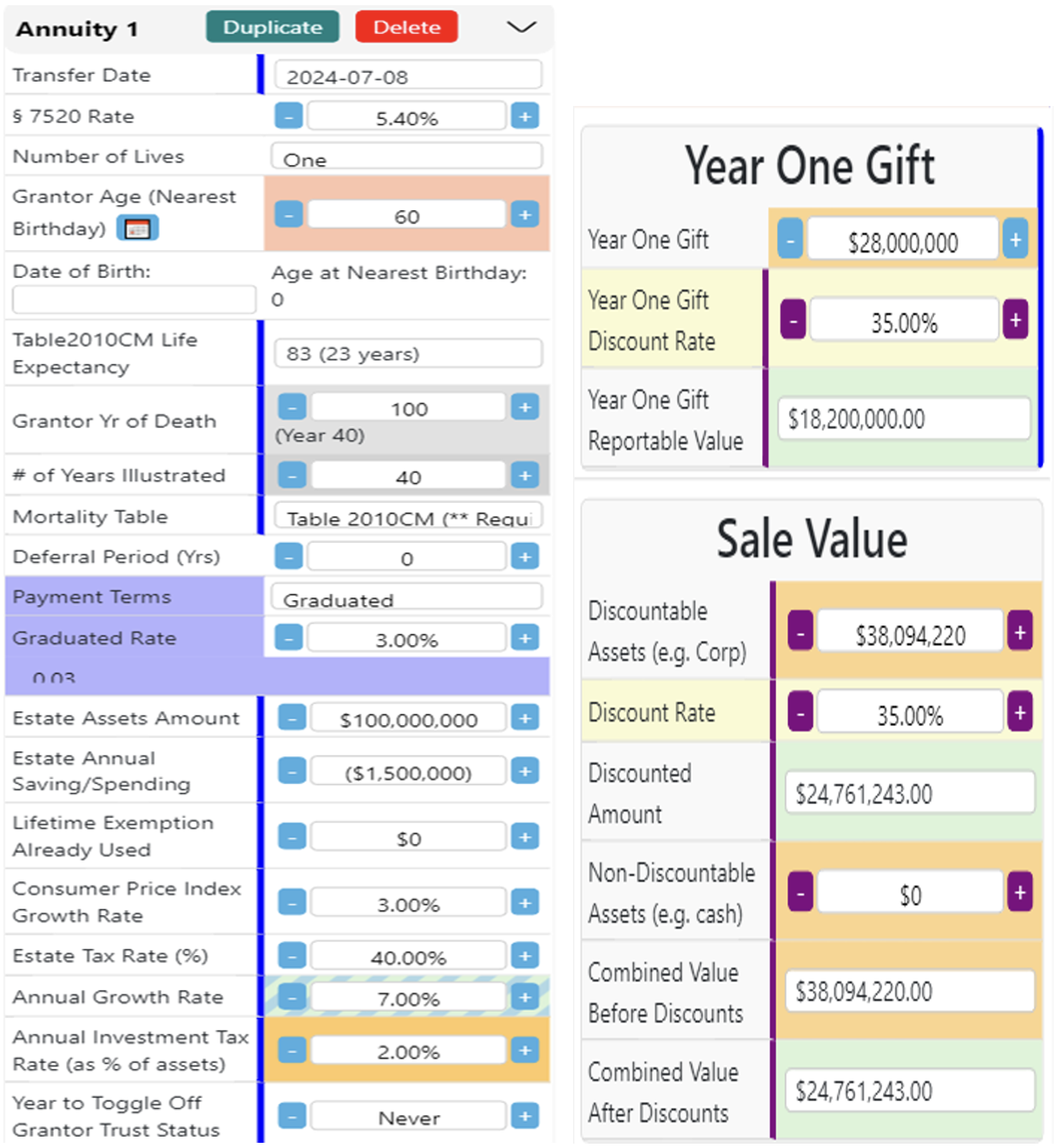

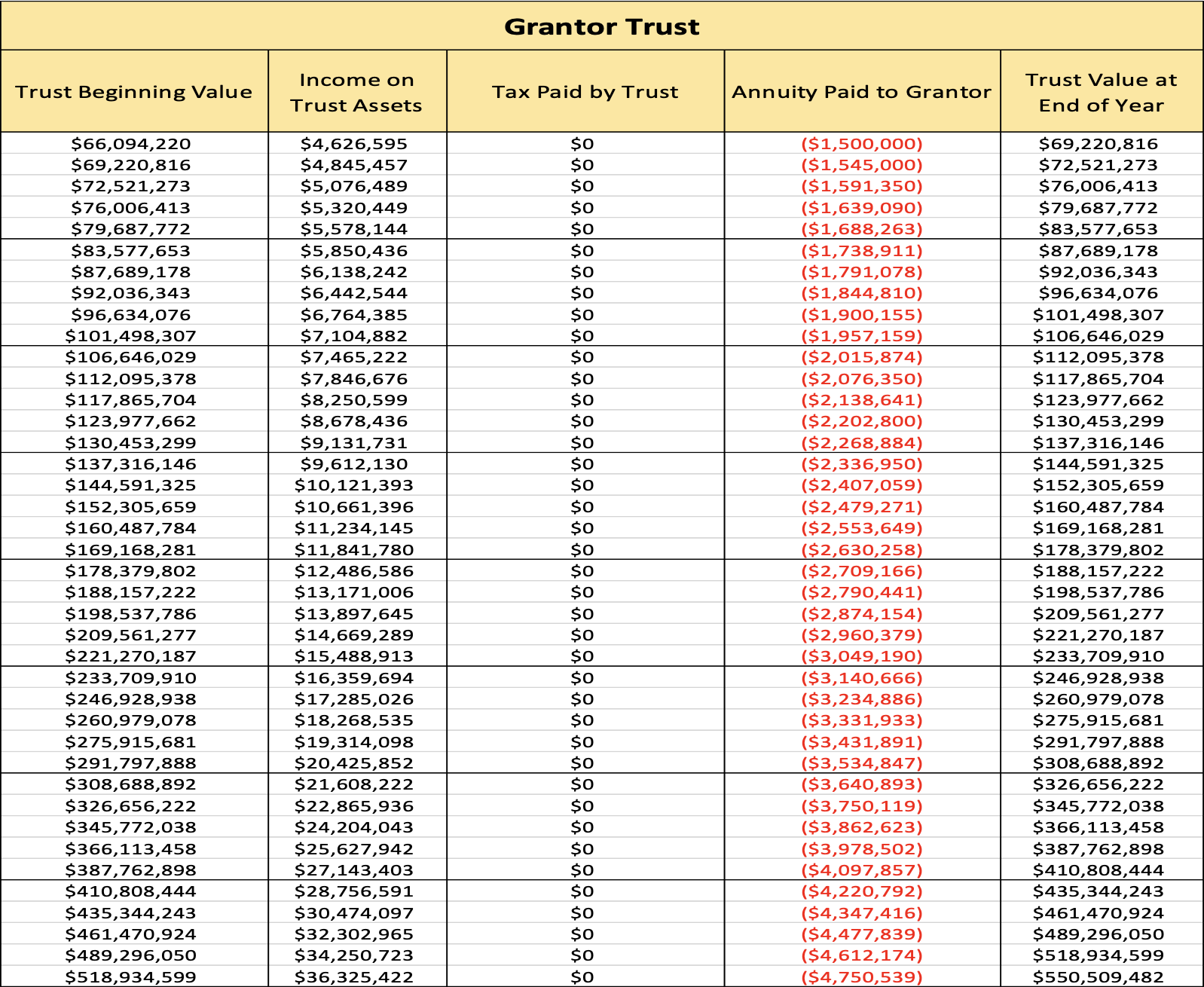

VII. Illustrating Private Annuity Sales

A. Private Annuity Overview

In a private annuity sale, Senior would sell his interest in an LLC, which may be a family business, to a Dynasty Trust in exchange for a right to a fixed stream of payments for his life. Typical considerations in a private annuity sale are as follows:

1. No gross estate inclusion

A properly structured private annuity is not included in the grantor’s gross estate under Section 2036(a)(1), as the right to the annuity is an obligation of the payor rather than a retained right described in Section 2036(a)(1).[16]

2. No gain recognition

Because the Dynasty Trust is a grantor trust with respect to Senior, the private annuity sale is ignored for income tax purposes.[17]

3. Gift tax can be avoided (if probability-of-exhaustion test satisfied)

The value of the private annuity can be determined using IRS actuarial tables, provided that there is not more than a 5% risk of exhaustion of the trust’s assets.[18] It is possible to avoid a taxable gift on the sale by setting the value of the annuity to be exactly equal to the value of the property sold.[19]

4. Estate tax efficiency if grantor dies prematurely.

Annuity payments end at death. Thus, if the grantor dies before receiving the actuarially expected number of annuity payments, the grantor’s estate is reduced, and additional property passes free of estate tax to the Dynasty Trust.

B. Why Even the Healthy Should Consider Private Annuities

Although commonly perceived as a bet on a shortened life expectancy, private annuity sales can be advantageous even when the senior family member is healthy. Considerations include:

1. Income security

By engaging in a private annuity sale, the senior family member is guaranteed a steady and predictable income stream for life.

2. Avoid valuation disputes.

A sale for full and adequate consideration need not be reported on a gift tax return, although adequate disclosure does cause the statute of limitations for assessment to begin running.[20] The assets sold in exchange for the annuity then pass free of estate tax and do not need to be reported on the senior family member’s estate tax return.

3. Psychological security to do more aggressive planning.

With the senior family member’s income assured, he or she may be prepared to do additional planning to deplete his or her estate, including by making large taxable gifts.

C. Private Annuity Sale to a Grantor Trust for Healthy Individuals.

Private annuities have historically been a niche estate planning strategy typically undertaken to capitalize on an individual’s relatively poor health. From an estate tax perspective, a private annuity shifts wealth from the senior generation (the one in poor health with a shorter life expectancy) to the junior generations in exchange for a promise by the junior generations to pay the senior generation an annuity that terminates upon death. The mutual promises, at least for gift tax purposes, typically have equivalent values. The gamble, at least from an estate tax standpoint, is that the senior generation will die before receiving the full benefit of the bargain.[21]

The purpose of this section is to examine the estate planning advantages achieved using a private annuity sale for healthy individuals who are expected to live to their actuarial life expectancy age and beyond and evaluate the circumstances when private annuity sales for healthy individuals are appropriate.[22] In order to eliminate the private annuity sale as an income tax realization event, the sale should be to a grantor trust.

The general actuarial assumptions cannot be used if the measuring life for the annuity is on an individual who is terminally ill.[23] An individual is considered terminally ill if there is at least a 50 percent probability that the individual will die within one year, but if the individual survives for eighteen months after the date the private annuity sale is completed, then the individual is presumed to have not been terminally ill.[24]

Since the use of a grantor trust as the issuer of the private annuity eliminates all the negative income tax implications for income taxable private annuity sales, the authors will focus exclusively on the estate planning advantages of grantor trust private annuity sales. As part of this analysis, the planner needs to evaluate how to financially structure the private annuity sale to coordinate the client’s financial objectives with the potential estate tax savings.

If the sale is to a grantor trust, there is never a sale for Federal income tax purposes.[25] Instead, the grantor of the trust (“Senior”) reports the income earned by the grantor trust’s assets throughout his/her life. Since the annuity obligation terminates at Senior’s death, there never is an income tax sale even though death terminates the trust’s grantor trust status. Thus, the trust has a transferred basis, even after the death of the grantor. Furthermore, it is still necessary to satisfy the minimum independent funding required by the legislative regulations promulgated by the delegation of rule-making authority under Section 7520(a).[26]

The Section 7520 rules were enacted in November of 1988 and effective after April 30, 1989, to authorize the Treasury Department to promulgate tables to be used to facilitate the valuation of annuity arrangements between related party taxpayers, and the valuation of term and certain other interests.

Before the enactment of Section 7520 the IRS provided guidance and tables for the valuation of private annuities in Revenue Ruling 77-454, which provided the original Exhaustion Test.

This test from Revenue Ruling 77-454, which was later enacted as Treasury Regulation provides that the transfer of assets in exchange for a life annuity will constitute a gift if the standard tables are used and the assets of a trust or other entity that is required to make the annuity payments are insufficient to satisfy the scheduled payments until the payee reaches age 110, assuming a rate of return equal to the Section 7520 rate that applies at the time that the annuity is established.

Failure to meet this test causes a gift to be considered to have been made which is equal in value to the present value of the payments in the future that would not be made if the trust that has earnings at the Section 7520 rate runs out of assets before the payee reaches the age 110.

An article by Kevin McGrath describing this rule, that was published in Tax Management Estates, Gifts, and Trusts Journal (2007), based its examples upon a Section 7520 rate of 5.2% (as of April 2025 the Section 7520 rate is 5.00%) and gave the example of a trust was funded with the proceeds of the issuance of a life annuity payable to an individual age 65 that was funded based upon the cost of the annuity pursuant to the tables plus an additional 10%.[27]

It can be challenging to fund a trust with sufficient assets to satisfy the exhaustion test, but it would appear possible to satisfy the test by having guarantees issued by one or more other trusts or individuals.

It would make sense to have a separate trust issue a guarantee to satisfy the exhaustion test so that the separate trust can toggle off grantor trust status to stop a substantial portion of “the burn.”

For example, a trust funded with $20,119,000 worth of assets in exchange for an annuity valued at $18,290,000 (to have 10% equity) that would pay $1,500,000 a year to an individual age 60 might benefit from a guarantee of payments from a separate trust funded in the amount of $5,563,000 dollars in order to satisfy the exhaustion.

Assuming that the first trust makes all of the annuity payments and grows at the rate of 7% a year, while the second trust simply grows at 7% a year without having any expenses, then in 20 years after the grantor has reached age 80 the first trust would have approximately $16.7 million of assets and could not be toggled off without causing the continued annuity payments to be subject to income tax, while the second trust valued at approximately $14.1 million could be toggled off, thus stopping approximately 46% of the burn in that year, assuming that both trusts have the same investment makeup.

The second question is whether the exhaustion test is valid.

There are two situations where healthy individuals should consider a private annuity sale to a grantor trust.

First, where the senior family member needs to continue to receive the income from the business as a source of funds for retirement, the private annuity provides the needed funds without exposing the source of these funds (the family business) to estate taxes. In effect, the senior family member can continue to rely on the family business for retirement while the family business will not be included in the gross estate.

Second, even if the senior family member does not need the income from the family business to provide for his support, the private annuity sale allows the sale of an income producing asset in return for the funds needed for living expenses for life. Most individuals feel a need to retain the assets needed to provide for their living expenses, with the result that this income-producing asset will be included in the gross estate at death. Given that the concern is to have the financial security of a source of funds for personal consumption for life, the private annuity is a viable alternative. Since the annuity payments will be consumed for living expenses, there is no concern about increasing one’s gross estate if they live beyond their life expectancy. And, having the security of knowing that there will always be an annuity to provide living expenses for life, individuals can be more aggressive in disposing of their other assets with other estate planning techniques. The ideal person for a private annuity is a married person with a net worth more than the transfer tax exemption who cannot afford to only retain assets equal to the transfer tax exemption. In other words, the individuals need to retain assets valued more than their transfer tax exemptions. The security of the private annuity for life allows the senior family member to dispose of other assets with a more aggressive gifting program that would otherwise be retained and exposed to the estate tax.

In passing the business on to the next generation, the funds needed by the trust to make the private annuity payments are from the profits of the business, or the growth of the income producing assets that were purchased by the trust. In effect, the sellers are now receiving the profits from the business indirectly instead of as the owners of the business. The estate planning advantage is that the income-producing asset, the business, is not exposed to inclusion in the gross estate. In effect, the purchased asset can supply the funds needed to pay the purchase price, the annual annuity,) without exposure to estate tax inclusion under Section 2036(a). The following example is intended to illustrate the advantages of the technique and can accomplish the communication objective.

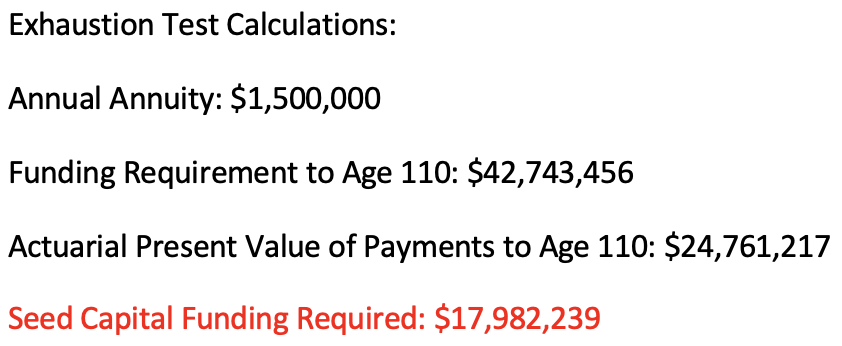

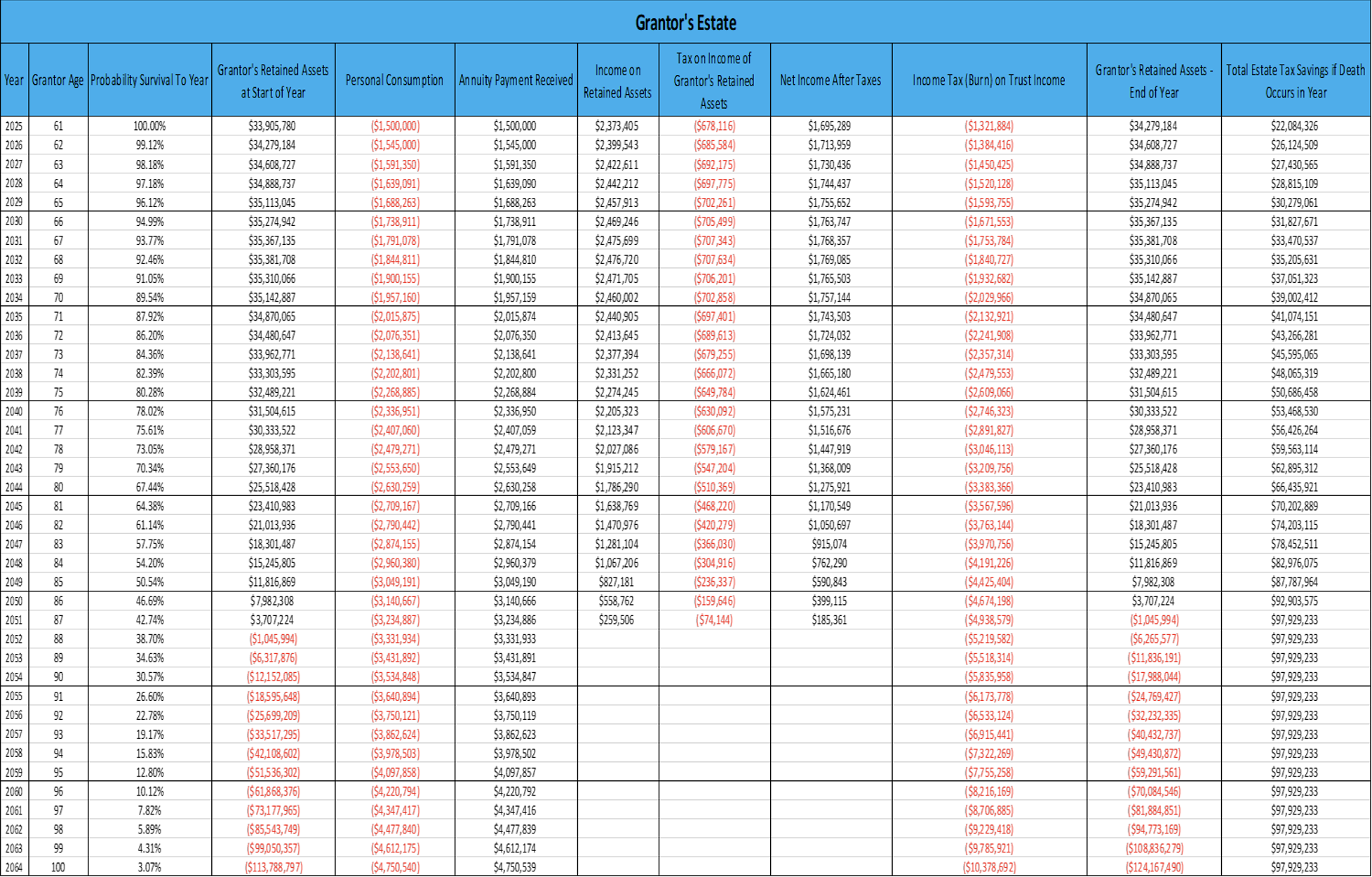

D. Example:

Assuming similar facts to the prior examples for the installment sale to a grantor trust, Senior has income producing assets valued at $100,000,000 and spends $1,500,000 a year on personal consumption. Senior desires to receive an annuity equal to his spending needs that adjusts for inflation at 3% annually. Senior therefore sells an LLC interest with a capital account of $38,094,220 to a Grantor Trust in exchange for a private annuity valued at $24,761,243 (assuming a 35% discount applies on the LLC interest transferred) that pays Senior $1,500,000 plus a 3% increase annually.

To satisfy the Exhaustion Test, the Trust must have additional assets of $17,982,239. If the Trust already has assets more than this amount, no additional transfer is needed, but assuming that that Trust is unfunded Senior transfers an additional LLC interest by gift with a $28,000,000 capital account valued at $18,200,000 assuming a 35% discount applies.

Senior retains approximately $34,000,000 of income producing assets.

The idea is that the annuity will provide Senior with annual payments to comfortably provide Senior with the funds needed for personal consumption. However, it is not that simple. One must also consider the impact of the Grantor Trust Burn!

Over the course of the next 20 to 25 years, the annual income taxes Senior pays, including the payment of the income taxes on the grantor trust’s income will fully deplete the annuity received and the income Senior earns on the retained income producing assets. As illustrated below, Senior’s retained assets are fully depleted at age 87, so this plan will need to be revised if Senior expects to live past the age of 87.

A summary of the transaction and illustrations are provided below:

E. Private Annuity Advantages

There are two advantages of a private annuity over a GRAT and an installment sale to a grantor trust. First, the payments provided by both the GRAT and the installment sale are designed to terminate while Senior is still alive while the private annuity can continue for the rest of Senior’s life. With the GRAT and the installment sale, the value retained is still included in the gross estate.[28] Where financial security is a concern, the SCIN is not a viable alternative as the payments will end at the end of the note term.

Even if Senior dies prematurely, the value of the closely held business is not exposed to estate tax. If Senior was in good health at the time the private annuity transaction occurred, it is unlikely that the IRS will argue that death was imminent, even if Senior dies before the 18-month safe harbor period.

An important factor often overlooked is the impact of grantor trust status as one must take into account that the grantor’s payment of the trust’s income taxes is a significant wealth depletion factor and can increase over time as the assets in the grantor trust accumulate from year to year.[29] As mentioned above, the funds needed to pay the trust’s income taxes can be provided by the income from the assets that Senior retained, and if that income is not sufficient, by a continued depletion of Senior’s retained principal.

F. Private Annuity Disadvantages

One obstacle for the private annuity is that the trust is required to have its own reserves (the seed money required by the exhaustion test), and that the seed money may have to be provided by a gift in trust. Otherwise, one will have to contend with the exhaustion test. For a GRAT the advantage is that the trust requires no seed money.

However, one must be careful of the judicial doctrines which allow the courts to disregard the reality of the private annuity transaction.

There are several cases in which the Tax Court has either re-characterized a private annuity sale to a trust as a transfer in trust with a retained interest,[30] or held that the trust was acting as a conduit for the taxpayer.[31] The Melnik, Stokes and Usher cases all involved fact patterns where judicial doctrines were imposed to disregard the private annuity obligation as a true debt obligation.

Properly structured private annuities, however, should not be includable in the grantor’s estate. According to the Supreme Court in Fidelity-Philadelphia Trust Co. v. Smith:[32]

Where a decedent, not in contemplation of death, has transferred property to another in return for a promise to make periodic payments to the transferor for his lifetime, it has been held that these payments are not income from the transferred property so as to include the property in the estate of the decedent. (Citing cases.) In these cases, the promise is a personal obligation of the transferee, the obligation is usually not chargeable to the transferred property, and the size of the payments is not determined by the size of the actual income from the transferred property at the time the payments are made.

The language used by the Supreme Court could pose a problem for many private annuity sales to trusts. If the trust has no other sources to make up any shortfall, such as a guarantee, in the trust’s assets to the annuitant, and assuming no guarantees are given so that no third party is liable to make up any such shortfall, and if the trust is minimally funded, then arguably the annuity is chargeable only to the trust assets.[33] In such a situation, the facts will not be viewed favorably by the IRS and Section 2036 exposure is significant.

CONCLUSION

As the examples demonstrate, the four wealth-shifting factors have a different financial impact depending upon how long the grantor survives and how they are used. As we saw, reducing the valuation discount permits the grantor to retain more income-producing assets. If a client wants to reduce the audit exposure by the IRS, one way to accomplish this objective is to use a lower valuation discount.

By changing the assumptions, the client can visualize their impact. The ability to immediately see the results from changing an assumption permits the client to participate in the decisions about how the four wealth-shifting factors are used.

In effect, the client participates in the design of the estate plan!

VIII. Appendix

Assumed Facts

- W age 60 H age 77

W’s investment assets $26,833,334

Investment rate of return 7.0%

Effective income tax rate 32%

Section 7520 rate 4.8% for September 2024